This is a remarkable collection of excerpts from some 180 authors, all but a few of them Germans born after the Second World War, reflecting from their various perspectives on the question: how could the Holocaust have happened in our country, among our people, in our culture? The predominant mood is that of deep self-examination, shame, and solidarity in guilt, with a fierce determination not to let go of the searing memories, and not to go on as if these things had not happened.

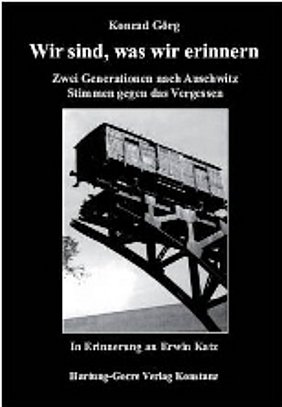

The book is the work of Konrad Görg, M.D., a specialist in hematology and oncology on the staff of Marburg University Hospital (born in 1953), who put together the collection as an exercise – a self-prescribed therapy, one might say – in his own personal effort to come to terms with the German past. He published the volume at the urging of friends, and it has now been translated into English by Fritz Voll of Toronto, Canada, the founder and long-time editor of www.jcrelations.net.

One of the notable features of the volume is that the story that it collectively tells does not begin in 1933, but rather traces the roots of German antisemitism back into the 19th century and before. Dr. Görg’s prefatory essay lists some of the elements of German political and cultural/intellectual history that contributed to the eventual catastrophe: "Lutheran submissiveness to authority, Prussian virtues of duty and obedience, German idealism’s alienation from reality, the irrationality of romanticism with its retreat into introspection, a Verjunkerung of the liberal bourgeoisie (meaning the influence of the landed nobility’s attitudes) during the Bismarck era, the monarchist-militarist constituion under William II, the lost First World War with all its burdensome consequences for the young republic and, not least, inadequately committed democratic awareness among the German population of the Weimar period."

The book includes quotes from victims, survivors, resisters, bystanders, and even perpetrators, both of the Holocaust itself and of the ever-tightening noose of anti-Jewish measures that preceded it. The Erwin Katz to whom the title of the book refers was a ten-year-old victim. "On the morning of April 18, 1944," his aunt recounts, "they came: a brutal gang of Hungarian policemen, armed with batons and machine guns. The Jews of the village were allowed just half an hour to pack up essentials." They ended up at Auschwitz, where Erwin and his mother and father were gassed on the night they arrived. His older sisters were assigned to a laundry crew and survived to tell the tale . Their main duty: removing the yellow stars from the coats of those that had been killed and burnt. And there are many more stories like this. "So together we wrest the nameless from anonymity" (Günther Ginzel, as quoted in the book).

One of the most affecting portions of the book is the tabulation, in an Addendum, of the specific anti-Jewish measures as they were promulgated. April 7, 1933: all Jewish civil servants dismissed. April 25: "Law against Overcrowding in German Schools and Universities" limits the proportion of Jewish students to 1.5%. September 29: all farmers must prove that they are racially Aryan. October 4: "Editors Law" excludes Jews from the press. February 5, 1934: Jews prohibited from becoming dentists or physicians. July 22: lawyers. December 8: pharmacists. September 15, 1935: "Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor" prohibits marriage between Jews and Gentiles. May 26, 1936: Jews expelled from the Chamber of Fine Arts. June 9, 1938: destruction of the synagogue in Munich. August 10: in Nuremberg. November 9-10: throughout the Reich. And so on and so on, carrying the story all the way down through the establishment of the concentration camps; the deportations; the establishment of the Einsatzgruppen ("Task Forces") to liquidate the Jews in the eastern territories; the gassings – not only at Auschwitz, but also at Chelmo, Treblinka, Belzec, Sobibor; the uprisings; the eventual liberation of the camps. Similar lists have of course been given elsewhere, but this one is unusually detailed.

Notable scholars and literary figures are among those quoted in the volume: Hannah Arendt, Yehuda Bauer, Ernst Cassirer, Paulo Freire, Ernst Jünger, Pinchas Lapide, Robert J. Lifton, Thomas Mann, Amos Oz, Paul Ricoeur, George Steiner, Fritz Stern, Paul Valéry, Elie Wiesel. Theologians cited include Reinhold Niebuhr, Johann Baptist Metz, Helmut Gollwitzer, Dorothee Sölle, and Helmut Thielicke. An extensive bibliography indicates the source of each quote.

This is a volume well worth reading and pondering. In addition to the printed version, it is also available as an e-book from Amazon.com.