This fascinating study sets out to analyze the diverse roles of Jesus in twentieth-century Hebrew and Yiddish prose and poetry. Stahl argues that in this literature, Jesus serves a range of ideological, aesthetic, political, social, and psychological functions that not only relate to the long history of Jewish-Christian relations in Europe, but also, and more importantly, reflect attempts to reframe Jewish identity in the move from the Diaspora to the land of Israel. Stahl probes the ambivalence towards Jesus: at the same time as he is inextricably bound up with the history of violence towards Jews committed in his name, he also represents an “authentic national Jew” whose resistance to the authorities of his time, and his suffering, exerted a powerful attraction to those involved in creating a new Israeli identity.

The introduction situates the study in its chronological, cultural, and geographical contexts with a brief overview of Yiddish and Hebrew literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the dramatic changes that began with the waves of Jewish emigration from Eastern Europe to the United State and Palestine in the aftermath of pogroms of 1881 and 1903. The main body of the book moves through twentieth-century Hebrew and Yiddish literature in more or less chronological order. Rather than provide a synthetic overview, however, the book adopts a more selective, and more interesting structure that alternates between thematic considerations and in-depth studies of individual authors and works.

In chapter 1, “A New Jew, A New Jesus,” Stahl argues that in Jewish literature of the early twentieth century, Jesus represented the dichotomy between the old Diaspora Jew and the new Hebrew, thereby reclaiming Jesus for Jewish nationalism as manifested in Zionism. For historian Joseph Klausner, Jesus exemplified the authentic pre-Diaspora Jew, a “native Jew” born and raised in Palestine (p. 16). Recruiting Jesus for the Jewish national project was an act of rebellion against traditional Judaism, which distanced itself from Christianity, its texts, and above all, its central figure. This view of Jesus emphasized morality over Christology, but also focused on Jesus’ suffering as symbolic of the Jewish people. In making this latter point, Stahl draws parallels between literature and visual art of the same period, especially the work of Reuven Rubin (1893-1974).

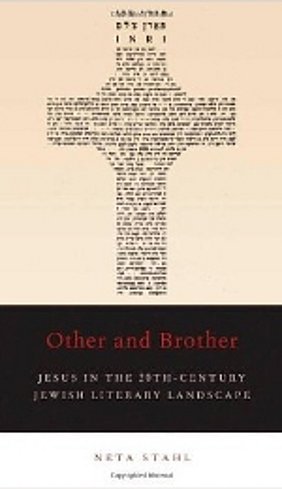

Chapter 2, “Cut off from all of his Brothers, from his Blood,” turns to the poetry of Uri Zvi Greenberg (1896-1981). Stahl argues that Greenberg uses the figure of Jesus to reflect his own biography and sense of self, including his experiences in the Austria-Hungarian army during World War I, the 1918 pogrom, immigration to Palestine 1923, and most important, the Holocaust. Greenberg’s poetry reflects both alienation from and kinship with Jesus, who is both indifferent to and symbolic of the suffering of European Jewry. Greenberg’s poetry incorporates Christian imagery not only verbally but also typographically, a point brilliantly illustrated in his poem “Uri Zvi in front of the Cross INRI” that is used to great effect on the cover of Stahl’s book. In the poignant poem “God and his Gentiles,” the Christian God descends from heaven, travels through Europe, laments the absence of his Jews, and is himself destined for slaughter due to his Jewish appearance. Whereas in other works the figure of Jesus is differentiated from his Christian interpretations, these poems suggest a bifurcation within the figure of Jesus himself, as both “Other” and “Brother.” This chapter provides several illustrations of Stahl’s incisive and beautifully written analyses of poetry.

Chapter 3, “Temptation of the Cross” examines the creation of the State of Israel as a turning point in modern Jewish literature. Stahl argues against the commonplace assumption that Jews dissociated themselves from Jesus after the Holocaust due to his associations with European anti-Semitism. On the contrary, post-Holocaust Hebrew literature appropriated and fully identified with Jesus. These authors detached Jesus from both nationalism and his first-century historical context, often using him as a symbol of the martyred artist, as in the biographical novel Life as a Parable (1966) by Pinchas Sadeh. The literature of this period, in contrast to prewar Hebrew literature, did not separate Jesus from Western culture but adopted those associations to express a longing for that culture by those who had made their lives in the fledgling Jewish state.

Chapter 4, “The Father and the Son of God,” concentrates on the writings of the Israeli prose-poetry writer Yoel Hoffman (b. 1937). Hoffman’s first book, Sefer Yosef (1989), a cross between prose and poetry, subverts the motif of the Holy Family by reducing it to a parent-child dyad. The single parent in this dyad functions as both mother and father whereas the son, Jesus, is both father and son. This usage, argues Stahl, neutralizes Jesus’ otherness and at the same time creates a longing for the missing member of the triangle. In this literature, Stahl notes, Jesus is able to bestow holiness on others: “the figure of Jesus is more than a brother; he is a savior, one who rescues the Others from their otherness, even as his presence confirms it” (p. 146).

Chapter 5 is called “Why have you forsaken them?” The replacement of the first-person singular used in Jesus’ last words (Matthew 27:46; Mark 15:34) with the third-person plural identifies the Jews’ suffering with Jesus’ own. The chapter is devoted to the poetry of Avot Yeshurun, in which Jesus becomes a nostalgic bridge to childhood and European Jewry. Stahl argues that in Avot Yeshurun’s work, in contrast to other literature she discusses, Jesus expresses the poet’s longing for his family, and, in particular, his excruciating guilt at having abandoned his family, who later died in the Holocaust. Jesus is not only the one who suffers, but also the one who abandoned the world to its demise (p. 153).

Thus far, Stahl has argued that for twentieth-century Jewish writers, Jesus for the most part mirrored the Jewish self, their longing for a homeland, their suffering in Eastern Europe and as artists, or their guilt in abandoning family and homeland for the land of Israel. In the epilogue, “The Ironic Gaze at Brother Jesus” Stahl turns the project back on itself by analyzing the ironic undercurrent of Jesus’ role in twentieth-century Jewish literature: the construction of Jesus as brother can never truly overcome his role as Other. Stahl argues that the very use of Jesus as a metaphor, symbol, or motif is ironic in that it implies two types of readers: those who recognize the irony and those who do not. This ironic usage may point to what Jewish authors truly thought about Jesus.

The irony comes to its most explicit expression in works which mock Jesus. The tradition of mocking Jesus begins with the medieval Toldot Yeshu texts, which ridicule the figure of Jesus by subverting the Christian narrative of Jesus’ infancy and passion. Twentieth-century authors who mock Jesus include Yiddish writers such as Melech Ravitch, Moshe Leyb Halpern, H. Leyvik, and Itzik Manger, who suffered in Soviet jails or Nazi ghettoes and concentration camps. They used the agonized Christian image of Jesus to give voice to their secular, humanistic worldview. In the works of Hebrew authors such as Shai Agnon and Hanoch Levin (1943-99), however, Jesus remains the “Other” in whom writers “found what was missing from their old Jewish Self” (p. 193).

Stahl’s analysis is compelling, and, like the literature it discusses, the book is elegantly written. Stahl develops an overarching chronological and thematic narrative, tracking the use of Jesus against the developing of Jewish identity in relationship to the suffering of European Jewry on the one hand and the nationalist Zionist project on the other hand. At the same time, she does not force all Hebrew and Yiddish literature into this mold, nor does she adhere to a simplistic distinction between Hebrew and Yiddish literature as such. Of course, there are always additional angles that might have been explored. Stahl mentions but does not develop at any length the question of whether and to what degree the Zionist use of Jesus was an element in the rebellion against traditional Judaism. Nor does she reflect on whether or to what degree Jewish authors drew upon the work of (primarily Christian) nineteenth- and twentieth-century historians who were exploring the historical Jesus within his own context. One might also wonder whether the positive appropriation of Jesus by Zionist authors was due precisely to their geographical relocation away from Christian Europe, where they were part of an often reviled minority group irrevocably branded as “Christ-killers.” Most of all, however, this book created a desire, at least on the part of this New Testament scholar, to read the prose and poetry that Stahl discusses and to encounter this Other Brother for herself.