In 1979, Pope John Paul II visited Auschwitz and characterized the site as the “Golgotha of the modern world.” (Carroll) As a highly visible Christian leader, his remembrance of the dead—more so his choice of the word “Golgotha”—was emphasized through the erection of a makeshift wooden cross. This particular religious symbol--as well as its location at Auschwitz--engendered controversy. Its sponsors were accused of “Christianizing” the Shoah.(Carroll) Furthermore, in Constantine’s Sword, James Carroll insists the cross has been the impetus to Christian animosity towards Jews. He chronicles repeated persecutions--directed at geographically disparate Jewish communities over millennia--all fueled by the accusation the Jews murdered Jesus. The debate places the cross squarely at the heart of anti-Semitism. The concerns emanating from Judaism are not limited to individuals directly linked to the Shoah. One should consider an earlier example, “Revenge of the Savior.”(Nirenberg) A Christian medieval tale, the story is a fanciful rendering of the Fall of Jerusalem. Claiming the Roman Emperor Vespasian was cured of a terrible illness by the burial shroud of Jesus, the story asserted Jerusalem’s fall was divine punishment--directed at the Jews—for crucifying Jesus. As the story goes, Vespasian claimed the surviving remnant of Jerusalem for himself. A portion was killed, but 180 survivors were banished to wander the empire under his protection—bearing the mark of Wandering Jewish Cains. Later, connecting the cross to the Shoah, Leon Wieseltier said, “No, Jesus on the cross…does not warm my heart…It is the symbol of a great faith…whose affiliation with power almost destroyed my family and my people.” (Carroll)

Aware of this sinister history, why would any Jewish artist depict Jesus on the cross, and thereby, in Plank’s words “confront a stronger taboo … borrowing … from the oppressor’s cultural tradition.” (Plank) Is it possible that a Jewish crucifixion genre is communicating a distinctly Jewish message? May it be “the cross functions not as an answer to atrocity, but as a question, protest, and critique of the assumptions we may have about profound suffering.” (Plank)

If this nexus is pursued, one artist figures prominently. Marc Chagall (1887-1985), raised in a Hasidic Jewish shtetl in Vitebsk, Byelorussia, painted the crucified Jesus in various works (Golgotha or Dedicated to Christ 1912, Falling Angel 1923, 1933, 1947, The Martyr 1940, Descent from the Cross 1941, White Crucifixion 1939, and Yellow Crucifixion 1943). His Jewish crucifixion genre was concurrent with pivotal historical events comprising repeated pogroms and the Shoah. In these works, Chagall conveys a seminal message. He artistically renders a Jesus who was the prototypical Jewish martyr. Through an unequivocally Jewish Jesus, he reminds Christians that it was the Jews who provided them with essentials for a nascent faith. Newer Testament Christology arose from the Hebrew Bible, preserved by Judaism despite murderous persecutions.

Interfaith healing and forgiveness may be informed by the Humanities, especially through Marc Chagall’s portrayal of a crucified, Jewish Jesus. Preliminary to study of Chagall’s cruciform oeuvre, historical background will be provided demonstrating how the cross has driven a wedge between Jews and Christians since the era of Constantine. A selection of other Jewish artists who influenced Chagall by using the cross as a muse will be reviewed for content as well.

I The Cross: from a Jewish-Christian Confluence to Persecutions

There were myriad Christian symbols representative of early Church History (First 4 Centuries C.E.). There was the acrostic ICTHUS (fish), the Anchor, and the Akedah—a divine sacrificial substitution for Isaac—as examples. (Goodenough, Hooke, Jensen, Olaru, Van Woerden) However, there is no historical mandate to suggest any of these, or others from the era preceding Constantine, orchestrated virulent anti- Semitic displays. In fact, the Akedah was shared by both Christians and Jews in catacomb art (as were images of Jonah, Noah, and Daniel)—equally representing the faith of the deceased from both religions until the Fourth Century C.E. (Goodenough) Before Constantine, catacomb art verifies that the earliest Christian symbolism was distinctly Jewish in character, separated only by novel reinterpret-tations of Older Testament events in light of Jesus’ life. The essence of a Christian-Jewish duality sharing of Older Testament content while respectfully maintaining 2 separate religious identities.

A catacomb discovered in the Via Latina in 1955 and dated on the cusp of the Constantinian shift—is rendered conspicuous by the complete absence of the cross and resurrection. It was comprised by rooms covered with paintings featuring Jonah, 3 young men in the furnace, Noah, Daniel, and Jacob at Bethel. (Goodenough) One uniquely Christian image reflected Jesus raising Lazarus. However, in the same scene, Moses is watching Jesus and is accompanied by a pillar of fire. A momentous Newer Testa-ment event was again accentuated its preceding Testament’s foundation. This motif is reminiscent of the Gospel accounts of the Transfiguration.

Another instance in which Christians reinterpreted distinctly Jewish symbolism is the aforementioned Akedah. In the 2nd century C.E., Melito of Sardis observed, “He bore the wood upon his shoulders as he was led up for the sacrifice like Isaac by his father. However, Christ suffered, but Isaac did not suffer, for he was a type of Christ who was to suffer in the future.” (Goodenough) Christians freely borrowed Jewish religious iconography as types for their new faith. These observations are not intended to com-pletely eliminate the cross from the early Centuries of the Christian Church. There is historical precedent demonstrating the cross’ presence as a Christian symbol prior to Constantine. (Longenecker) There is also evidence that it framed an anti-Semitic animus. In 167 C.E., the same Melito preached a homily on the Passover. He intimated that by crucifying Jesus, the Jews murdered God and that all Jews were guilty of the crime. (Goldstein) Since Christians of the time were still a disempowered sect in the Roman Empire, the actual persecution of Jews contingent on the Cross awaited Constantine.

After Constantine’s ascent to power, the cross catalyzed a redundant dynamic. Chrysostom accused the Jews of assassinating Jesus. (Goldstein) Ambrose justified the burning of synagogues for the same reason. (Goldstein) But it took the Crusades to cement the symbol of the cross to the wholesale slaughter of Jews by Christians—an archetypal Shoah. These first organized large scale Christian killers of Jews wore a cross on their shields. (Carroll) The Crusader Godfrey of Bouillon vowed to avenge the blood of Jesus by leaving no member of the Jewish race alive. (Goldstein) Although the Crusades were ostensibly to free the Holy Land from Islam, quotations from participants demonstrate an anti-Semitic fury finding its source in the crucifixion of Jesus. “We take our souls in our hands in order to kill and subjugate all those kingdoms that do not believe in the crucified. How much more so (should we kill and subjugate) the Jews, who killed and crucified him…’(so) they…placed an evil sign upon their garments, a cross.’ ” (Carroll) On the first Crusade, the Crusaders “attacked them (Jews)…they broke into the Jews ‘strong house’ and threw the Torah scrolls to the ground. They tore them and trampled them under foot.” (Carroll) The number of Jews murdered or forced to suicide in those weeks is estimated to be as high as 10,000, which may be one third of the Jews living in the northern Europe at that time. (Carroll) Although a common respect within a duality of shared symbols exemplified the early Common Era, from the time of Constantine through the Shoah, the cross/crucifix has ignited the persecution and murder of Jews by Christians.

II Nonetheless: The Cross of Christ Appears in Jewish Art

“Late nineteenth and twentieth Century Jewish painters and sculptors were exploring … the crucified Christ … Crucifixion of the Jewish Jesus was transformed into an expression of Jewish uffering … Europe of the late Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries saw a Jewish attempt to highlight the Jewishness of the historic Jesus." ( Rizzolo)

“In 1942, the Puma Gallery in New York City hosted an exhibit entitled ‘Modern Christs.’ Of the 26 artists showing works, 17 were Jewish, a startling number.” (Hayman)

Depicting the crucifixion through the visual arts was not unique to Chagall as a Jewish artist and he did not originate the oeuvre. He had influential predecessors. Importantly, these individuals led him to his genre portraying an explicitly Jewish Jesus who exemplified tolerance. Jesus’ suffering as a Jew was a message to his followers regarding their behavior towards the Jewish faith. Although Chagall was born Moishe Chagall, after his relocation to Paris in the 1940s, he changed his first name to Marc out of respect for Marc Antokolsky, a prominent Russian-Jewish sculptor. (Kravitz) Antokolsky’s Ecce Homo was a renowned statue of a Jewish Jesus with side curls and skull cap. (Amishai-Maisels) Antokolsky’s personal letters made it clear that Ecce Homo was his artistic response to the pogroms perpetrated in Russia (1871). (Amishai-Maisels) He was reminding Christians that Jesus was Jewish and persecution of his people was a perversion of his teachings. (Amishai-Maisels) Chagall was aware of Antokolsky’s corpus. In the words of Maisels, “he (Chagall) suggested that a Jewish artist’s goal in Russia was to be a future Antokolsky.” Furthermore, Chagall’s friend Ilya Ginzberg had been Antolkolsky’s assistant and could give Chagall a vicarious intimacy with the master. (AmishaiMaisels). In similar manner, Moses Jacob Ezekiel an American Jewish sculptor reacted to pogroms in Eastern Europe (Rizzolo). Other exemplary names included Jakob Steinhart, Mordechai Moreh, Mordechai Ardon, and Ben Sahn. (Jeffrey). There also was a genre of Jewish poetry that used the crucifixion to communicate important messages. Uri-Tsvi Grinberg who left Germany with his family for Palestine in 1924 was a Jewish Expressionistic poet. (Harshav). He once wrote, “At the Churches, Hangs My brother, Crucified…Brother Jesus, a Jewish skin-and-bones…At your feet: a heap of cut-off Jew heads. Torn talises…Golgotha is here: all around.” (Harshav) The heap of Jewish heads refers to pogroms contemporary to the poet. In fact, Marc Chagall himself wrote poetry that included the cross. He observed (Barta), “For me Christ was a great poet, the teaching of whose poetry has been forgotten by the modern world. He waxed poetically,

I carry my cross every day,

I am led by the hand and driven on,

Night darkens around me.

Have you abandoned me, My God why? (Jeffrey)

As an extension of his forerunners, Chagall’s Christology emphasized the crucified Jesus’ Jewishness.

After October 15th, 1930 when the Reischstag unveiled its plan to persecute the Jewish community, Chagall wrote, “A Jew passes with the face of Christ/He cries: Calamity is upon us/Let us run and hide in the ditches.” (Amishai-Maisels) And, “For me, Christ has always symbolized the true type of the Jewish martyr. This is how I understood him in 1908 when I used this figure…(Golgotha)...under the influence of the pogroms. Then I painted and drew him in pictures about ghettoes, surrounded by Jewish troubles, by Jewish mothers, running terrified with little children in their arms.” (Amishai-Maisels) It will also become apparent with further study that Chagall blended Jewish and Christian symbols and iconography to remind Christians of the common eschatological expectations of final redemption shared with Judaism.

III Chagall’s Crucifixions: His Artistic-Theological Message

“Chagall did not just use the Crucifixion as a general symbol of the Holocaust, but added details relating to specific events. As in 19th century Jewish polemics, the stress here is Christ's poetry being forgotten by the modern world, which ignores his teachings and persecutes his people.” (Barta )

In addition to the observation that Chagall portrayed a Jewish Jesus—there are other powerful messages imbedded in his works. Similar to the early Common Era sharing of religious symbols between Jews and Christians--with each perspective maintaining a unique religious identity—he revisits this arena and uses his brush to create a Jewish-Christian dualism comprised of suffering and future hope. (Barta) Further study of 3 of Chagall’s Crucifixion paintings will focus and expand these propositions.

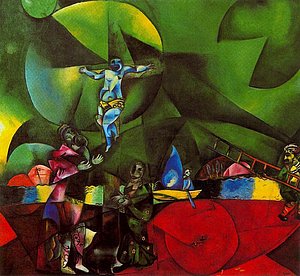

IV Golgotha (1912)

In 1911, Mendel Beilis, a Jew, was accused of murdering a Christian child and using his blood for ritual purposes—the Christian excuse for Jewish persecutions--the recurring blood libel. (Rizzolo, Goldstein, Nirenberg) In response, the focus of the painting Golgotha by Chagall is the crucified Christ child. Note that the ladder to the cross is being removed. Will the crucified Christ child hang on the cross forever? The ladder also engages the typology of Jacob’s ladder, appropriated by Christianity after Jewish description. The sketches for the painting had Chagall’s name on the cross above the Russian equivalent for INRI, so that by substituting his own first name in Hebrew above…Chagall made it clear that the child is not Christian but Jewish.” (Rizzolo) The sketch thus reverses the blood libel directed at Beilis, a Jew. It is a Jewish child, Chagall-Jesus, who is killed for ritual reasons by Christians--not the opposite. Parents in the traditional garb of the time stand on blue ground stained red with the child Jesus’ blood. (Rizzolo) The work was responding to chronologically proximate Russian pogroms. (Amishai-Maisels).

V WHITE CRUCIFIXION (1938)

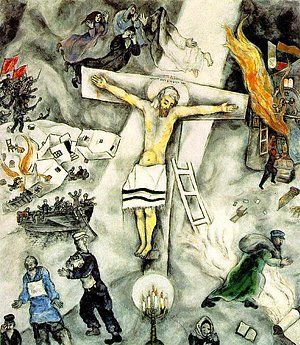

“ In the chaotic world of the White Crucifixion, all are unredeemed … (a) vortex of destruction binding crucified victim and modern martyr… Christ and Jewish sufferers are one.” (Plank)

“Amidst this devastation, Jews flee in all directions, attempting to escape with their most valuable possessions…a villager, sadly looking back on the ruin, also flees, clutching his most prized possession, a Torah. He wears only 1 shoe (left lower corner)…He could live without his shoe, but not without his faith.” (Kravitz)

This unmistakably Jewish Jesus is surrounded by Jewish suffering contemporary to Chagall. The Nazi at the burning ark (right upper corner) symbolizes the destruction of the Munich and Nuremberg synagogues on June 9th and August, 10th, 1938.(Amishai-Maisels) The 'Ich bin Jude' sign (left lower corner) derives from German attempts to brand Jews in mid-1938.(Amishai-Maisles) But there was more to come. On November 10th, 1938, the date of infamy for Kristallnacht, Jewish graves were desecrated and German Jews arrested and in Germany and deported to camps on what has been identified as “the inception of the Holocaust.” (Kravitz). In fact, Kristallnacht was anti-Semitism augmented by political power and expressions of mass hatred. (Kravitz) Also disconcerting, a predominantly Christian Europe did not seem take notice. (Kravitz) In this work, the Torah is the anchor point for motion. At the top right, a soldier sets the Torah and a syngogue on fire. At the bottom a man hugs Torah on the left, while on the right, another man runs towards a Torah scroll. A Jewish deceased person lies unburied (left middle), a sacrilege. At the bottommost right, a desperate Jewish mother is seeking eye contact as she clutches her baby. Her image is universally understood--by Jews, Christians and other Gentiles--as there is little in life that is as pure…as a mother’s love for her child.“ (Amishai-Maisels, Rizzolo, Barta) The central focus however, is the crucified Christ. Directly to the left of Jesus’ outstretched arm, is the burning synagogue. Reminiscent of an earlier quote engaging the Crusades, sacred contents of the house of worship are strewn beneath the soldier’s feet. Hovering above the scene are four biblical figures mourning the death of Jesus and his fellow Jews. Their presence is predicted by a Jewish legend.

After the destruction of the first temple, God called Moses and the Partiachs to share his grief since they knew how to grieve. (Amishai-Maisels) At the left is Rachel crying for all her children. The boat on the left has only 1 oar. Escape is unlikely. An important duality follows connecting both Jesus to the Jewish faith and Christians to Jews. The light from above the cross—the Christian nimbus--meets the light coming from the Menorah. Jesus wears a loin cloth that is unmistakably a tallith. Above his head is the inscription, INRI: J(I)esus, Nazarenus, Rex J(I)udaeorum in Aramaic as Yeshu HaNotrzri Malcha D’Yehudai written in Hebrew characters. (Barta) Chagall’s spelling of HaNotrzri implies Jesus the Christian more than Jesus the Nazarene. So Jesus the Christian and King of the Jews belongs to both faiths. (Barta) Whatever the cross of Christ has meant throughout a long history, Chagall appropriated to inform responses and responsibility during Genocide. It is symbol of suffering and hoped for redemption. In this particular painting of unmitigated suffering, Jesus is with persecuted Jews.

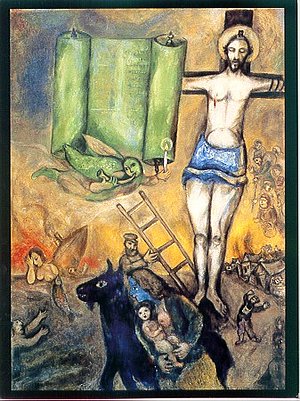

VI YELLOW CRUCIFIXION (1943)

"Jesus wears phylacteries (not a crown of thorns)…and an open Torah scroll covers his right arm. This scroll, illuminated by a candle held by an angel who blows a shofar, the symbol of redemption. (The) “Concept of atonement…in such small details…’On the Day of Atonement you shall make the shofar to sound throughout your land…and you shall proclaim liberty throughout all the land.’" (Jeffrey)

In this work, the cross is planted in a burning shtetl from which Jews are trying to escape. Again there is implied dualism, Jesus “…has both Jewish phylacteries and a Christian nimbus,” joining the Torah and Gospel. Despite suffering and anguish (see the man on the right), the angel blows a shofar (under the Torah scroll). (Barta) In the painting, Jesus’ sacrifice is joined to its original proclamation in the Torah so that in the words of Barta,

“the heart of the Christian Gospel to be seen as at one with the Torah and its hope of fulfillment…(the) Biblical Yom Kippur and Golgotha … are paired. (Barta)

Although Christian critics see the typological connection between the Shofar’s use at Jubilee and Jesus’ setting the captives free on the cross (Jeffrey), the shofar expresses a diversity in symbolism for Chagall’s Jewish audience. The Shofar was sounded as the trumpet of coronation, also as the sound to awaken conscience. The Shofar was a reminder of the Sinaitic Covenant, the words of the prophets, the destruction of the Temple. It was a call to renew freedom, a reminder of the Akedah (see below), the Day of Judgment and the Eschatological Proclamation of one God as King. (Miller) Two trenchant quotations expand the symbolism of the shofar to suffering—even the horrible suffering and pain of the Shoah--and prayerfully express it transcendently.

“There is a sense of expectation in the silence before the shofar sound … Part of its mystery lies in the interplay of the silence, the piercing sound, and the hum of people praying … the shofar can…express what we cannot find the right words to say. The blasts are the wordless cries of the People of Israel. The Shofar is the instrument that sends those cries of pain and sorrow and longing hurtling across the vast distance towards the Other.” (Michael Strassfeld)

“the musical potency of the instrument…which transcends any purely functional role and underlines a capacity to elicit spiritual experience.(It) reinterprets ancient notions of national identity, destruction, loss, hope, and redemption within the communal and personal context of Jewish History….with its dual aspect of destruction and redemption … there is the same ‘religious-magical awe’…the same faith in the shofar’s power to subdue the mightiest forces of nature and overcome the greatest evil…a potent symbol, like the signal of dawn over Jerusalem, to express faith in a new dawn for humanity. (Malcolm Miller)

On Rosh Hashanah, the blowing of the shofar is to remind the Jewish people of the future promises of Redemption. From Isaiah 27:13, “a great ram’s horn shall be sounded…(they) shall come on and worship the Lord…in Jerusalem.” (Rosenbloom)

The green color of the work symbolizes hope. Chagall is essentially “reappropriating the central Christian symbol of the crucified Savior to the site of its historical foreshadowing in historic Jewish experience. Chagall is deliberately reversing the polarity of type and ante-type as developed in Christian tradition…to achieve a simultaneous celebration and integrative re-interpretation of both Jewish and Christian sources of consolation.” (Jeffrey) Echoing Jeffery’s sentiment, Barta observes,

“I argue that the motif of the crucifixion for Chagall is not merely a pictorial representation of the ultimate suffering of the Jews. Rather, as a Jew deeply imbued with a sense of the importance of the Torah…Chagall views the crucifixion motif both as a symbol displaying the suffering of the Jewish people and as image exemplifying the ideals of Christianity.”(Barta)

VII Chagall’s Message: Heirs to a Promise of Redemption

“Both Judaism and Christianity consider themselves to be heirs to the promises given to Abraham and Isaac… As brothers often do, they picked different, even opposing ways to preserve their family’s heritage. Their differences became so important that for 2 millennia few people have been able to appreciate their underlying commonalities and, hence, the reasons for their differences.” (Carroll)

Chagall’s crucifixion genre should awaken Christian reflection on the Shoah as well as a disturbingly lengthy history of Jewish persecution. By emphasizing Jesus’ Jewishness, Chagall reproaches Christians for their commissions and omissions towards the Jews. In the he words of Amishai-Maisels,

“Although for many Jews such a portrayal of the (crucified) victim in the guise of the religious symbolism of his persecutor is profoundly disturbing, few other symbols offer such a wealth of associative meaning, or the ability to address and condemn the Christian world simultaneously.”

Although Chagall was one of many Jewish artists utilizing the crucifixion as a message to Christians, he has unique additions to the oeuvre that should be appreciated. His reversal of religious typology—juxtaposing the redemptive power of the Torah and the Gospel—is sui generis. In the Yellow Crucifixion, having the Jewish Jesus’ crucified hand touch the Torah connects Christian and Jewish future hopes in a way no other image can.

In a practical manner, interviews of rescuers during the Shoah add further to Chagall’s message. The forgotten kinship between Christians and Jews caught the attention of Christian rescuers during World War II. When asked why they risked their lives for Jews, they responded,

“We were brought up in a tradition in which we had learned that the Jewish people were the people of the Lord.“ (Gushee)

Chagall has proven once again that “visual art often serves as a highly sophisticated, literate, and even eloquent mode of theological expression.” (Jensen)