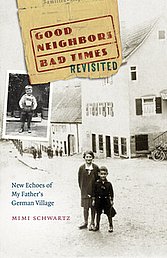

His letter came from South Australia, out of the blue. He wanted to thank me for my book about Christian and Jewish neighbors in the tiny German village of Rexingen, where my father’s family was from. “Your father was right,” his letter assured me, “we all got along before Hitler.”

This man, Max Sayer, was 88 and had grown up five houses from where my father’s family had lived for generations. Max’s Catholic family moved into their house in 1937, a few months after my uncle Julius, the last of our Jewish family to leave Nazi Germany, had sold our family’s house and fled to America.

I wrote back wondering who this Max was and whether his family really “did what they could” during the Hitler years. That’s who I was interested in: the Christians who were remembered as trying to help their Jewish neighbors. Who were they? Why did they do it? And were these collective memories of “good” Christian neighbors even true?

The catalyst for my asking was a village Torah, charred and with knife slashes, that I’d seen in the Memorial Room in Shavei Zion, an Israeli village north of Haifa that was founded by a small group of Rexingen Jews who had fled Hitler. The old man showing me around said the Torah had been saved on Kristallnacht — when the Nazis burned synagogues all over Germany — and that it had been rescued not by the Jews but by their Christian neighbors. I was surprised. I didn’t think of Germans as saving anything Jewish back then.

That’s when an echo came back from my childhood in Queens, New York, where I grew up. It was my father telling me how, as a boy in Rexingen, 30 years before Hitler, “we all got along.” Half the village of 1,200 was Jewish then; the other half Catholic, with a few Protestant families. Did some of the good neighbors before Hitler save the Torah during Nazi times?

To find out, I sat in dozens of living rooms — first those of the Jews who fled and resettled in New York and elsewhere, then of their former Christian neighbors who were still in the village. The village’s sole policeman, it turned out, saved not one Torah but two. (The other is in Burlington, Vt.) But no one could save any of the 87 Jews born in Rexingen who were deported and murdered. Hiding in a small village was impossible, people agreed. As my father liked to say, “Everyone knew what was cooking in everyone else’s pot.”

Instead of heroic acts, I learned about small gestures of decency, like delivering soup over a fence at night; sharing a ration card; cutting Jewish hair despite the sign “No Jews or dogs allowed.” Things I hope I would risk for a neighbor under threat — although you never know, do you? Those I interviewed told me of a few who “got into trouble,” some with severe warnings, one who disappeared for several days after allegedly driving a Jewish family to the Swiss border. That man, a taxi driver, never talked about it.

Was Max’s family one of the helping families I overlooked or had they largely gone along with Hitler? I kept wondering.

A week after I wrote to Max, his son Mäxle sent an email saying his dad was thrilled to hear from me. He included an excerpt from his father’s private memoir of his boyhood during the Third Reich, describing the day after Kristallnacht:

. . . when we kids came home from school, we sneaked inside to have a look — the first time ever I set foot into a synagogue. There were books laying around everywhere and I picked up part of a Torah scroll to take home, but when I came home Mum sent me straight back to return it. The air was still full of smoke and wet paper and material — it didn’t smell like a Christian church at all, the whole thing looked very sad.

My first reaction was: He took a souvenir? I squirmed until I realized he was an 8-year-old kid — I could imagine doing the same thing in his shoes. Binary labels of “good German” and “bad German” turned into a three-dimensional person writing with unguarded honesty from a young boy’s perspective.

Whatever Max’s family’s past, I needed to understand it, especially since his letter came the same week that 11 Jews were murdered in the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh. The past had moved in closer.

I asked if Max would share his whole memoir, and a week later 137 pages, written over 20 years, were in my inbox. I read about Max, at 5, enjoying his first Hitler parade. And Max joining the Hitler Youth at age 10 and proudly becoming its leader. And Max confused about how to be both a good Catholic boy and a good Hitler youth. And Max loving trains, an anathema for Jews as the symbol of deportation and death.

But here also was Max going weekly to light the Sabbath fires for the three elderly Jewish ladies next door. So he did help too! And Max’s father joining the SA (the Nazi’s paramilitary storm troopers) in 1926 — but then quitting in 1937, because he didn’t like the anti-Semitism against Jews he knew. More ambiguities. On what moral scale do you weigh a child living in the Third Reich? Or his parents whom you cannot know?

Over the next year, an unexpected trust grew between Max, his family, and me. I asked follow-up questions, often uncomfortable ones: Why did you go to the Hitler school? Did you ever have a Jewish friend that you helped or abandoned? And Max — or Mäxle — answered.

I looked into publishing possibilities for Max’s manuscript. We gathered photos and did research for each other. And we discussed including excerpts of Max’s memoir in a book, one that would capture his memories talking with mine, as if out of different windows of history.

What could have become tense and closed was, instead, negotiated with civility and caring. Gradually, my need to judge his family’s past faded — and without my feeling any pressure to forgive or to pretend to forget the millions who were killed. At one point Max was ill in the hospital, and I asked Mäxle, “Should I still be asking questions?”

“Yes, please do, it’s what keeps him alive,” he responded. That was a gift to me.

A year later, Max and I finally “met” on Zoom, together with his wife, Bernice, their three adult children, and a few grandchildren popping in on their way to soccer and dance class. We all talked for an hour, South Australia to New Jersey, as if after 83 years, we were next door, exchanging stories across oceans and time, as virtual neighbors, helping each other out.

“Mimi Schwartz brings us back to her father’s ancestral village of Rexingen in the German Black Forest to show us that, generations later, it still has much to teach us about decency then and now.”

“Mimi Schwartz brings us back to her father’s ancestral village of Rexingen in the German Black Forest to show us that, generations later, it still has much to teach us about decency then and now.”