In his Guide of the Perplexed I:27, Rambam (Moses Maimonides, 1138-1204) wrote:

Onkelos the Proselyte was highly adept in Syriac and Hebrew. He made it his aim to purge corporealism, substituting fit glosses for any biblical predicate suggesting God’s embodiment. Wherever he finds a term for motion of some kind, he takes it to mean an effulgence of created light manifesting God’s Shekhinah or Providence.[1]

Targum Onkelos, an ancient Aramaic translation (targum) of the Torah, has attained a quasi-canonical status in Jewish tradition. Many editions of the Pentateuch, even if they include no other commentaries, include Targum Onkelos, and there is a custom on the eve of the Sabbath on Friday evening to read the weekly Torah portion, each verse twice in Hebrew and in Targum Onkelos once. Nevertheless, despite its status, there remain many unresolved questions among scholars regarding:

- the date of the Targum

- whether it was redacted in the Land of Israel or in Babylonia

- western vs. eastern Aramaic linguistic features

- was there an individual Onkelos who was a proselyte

- or did Babylonian Jews simply misunderstand a reference in the Jerusalem Talmud to a Greek translation by Aquilas the Proselyte, a relative of Hadrian and student of Rabbi Akiva, and attributed their existing Aramaic translation to “Onkelos”?[2]

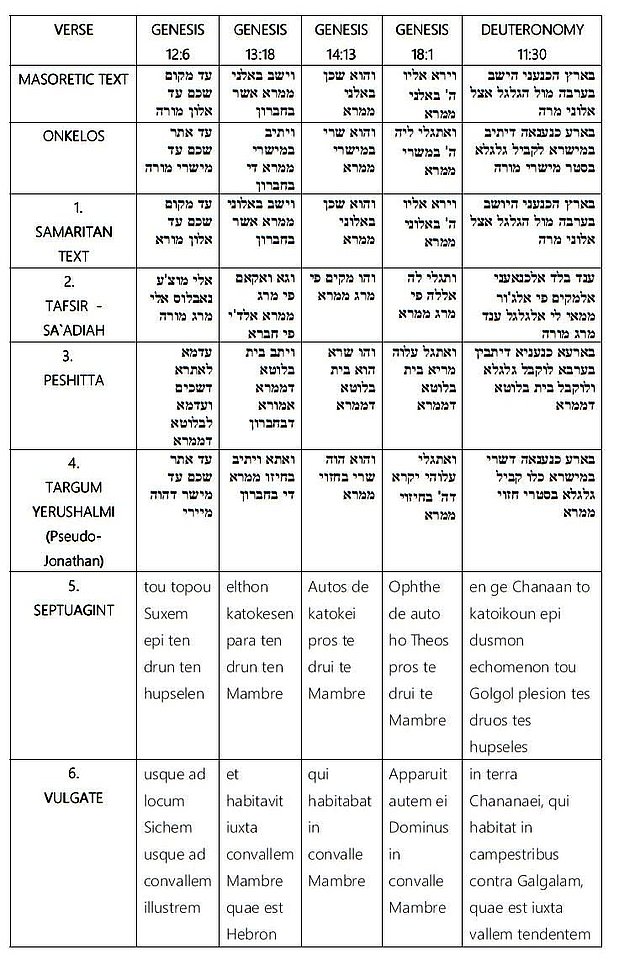

As we shall see below, one of the strange features of Onkelos is the translation of the plural construct elonei (some kind of tree, often translated as a terebinth or oak) in elonei mamré (Genesis 13:18, 14:13, 18:1) and elonei moreh (Genesis 12:6 and Deuteronomy 11:30), whether in the area of Shechem in the north, or of Hebron in the south consistently as meisharei (singular: Hebrew meishor, Aramaic meishara or meishra), meaning a plain or valley.

Assuming that Rambam and those who agree with him are correct that Onkelos sought to avoid or soften anthropomorphisms and anthropopathisms in the biblical text, what is the problem with these geographical references to a tree or trees in a certain place known in those days, which would seem to be the text’s obvious meaning? Why is a plain preferable to a tree?

In his commentary to the first of these passages (Genesis 12:6), Nahum Sarna wrote:[3]

The Hebrew ’elon moreh, undoubtedly some mighty tree with sacred associations. Moreh must mean “teacher, oracle giver.” This tree (or a cluster of such trees) was so conspicuous and so famous that it served as a “landmark” to identify other sites in the area. The phenomenon of a sacred tree, particularly one associated with a sacred site, is well known in a variety of cultures . . . It is a bridge between the human and divine spheres, and it becomes an arena of divine-human encounter, an ideal medium of oracles and revelation. Fertility cults flourished in connection with such trees, and this form of paganism proved attractive to many Israelites. For this reason, the official religion of Israel forbade the planting of trees within the precincts of the altar, as stated in Deuteronomy 16:21.

Sarna then listed additional cultic associations with the tree(s) near Shechem in Genesis 35:4, Joshua 24:26, Judges 9:6, 9:37.

In their commentary to their 5-volume English translation of Onkelos, Israel Drazin and Stanley Wagner suggest that such pagan associations with cultic trees may have led Onkelos to translate eilon and eilonei not as tree(s) but as a plain or valley.[4]

Plain of Moreh. The Bible’s eilon is usually translated “terebinth,” which is a tree. This might suggest to some readers that Abram settled in the midst of tree worshipers, since the worship of trees was quite prevalent during Abram’s lifetime and for many centuries after his demise. Onkelos – like Saadiah, Pseudo-Jonathan, the Samaritan Bible, the Septuagint, and other ancient versions – removes this possible misconception and renders “plain.”

Regardless of the larger question whether this concern for pagan and idolatrous associations was, in fact, the reason for Onkelos’ rendering eilon/eilonei as a plain, on a purely textual level, an examination of various ancient versions requires us to adjust that blanket statement. Some versions agree, more or less, with Onkelos, others do not, and retain the literal translation as “tree(s),” as the table below shows.

- The Samaritan text makes no substitution; except for some minor orthographic differences, it is identical to the Masoretic text.

- Sa`adiah Gaon’s Arabic Tafsir translates the passages in Genesis a marj, meaning a meadow or pasture land, perhaps for a usage similar to “plain” or “valley” in Onkelos. The passage in Deuteronomy, however, renders it as ghaur, which also means a lowland or valley or pasture-land. However, the Arabic term is also a designation of that part of the Syrian-African rift which constitutes the Jordan valley.[1] Whether this geological term existed in his day and Sa`adiah was familiar with it, and whether his translations reflect a concern for possible pagan associations with cultic trees, as suggested by Drazin and Wagner in the case of Onkelos, is by no means clear or certain.

- The Peshitta consistently retains the meaning of an oak tree לוטא

- Targum Yerushalmi (Pseudo-Jonathan) also has מישרא, מישר like Onkelos, but only in two passages (Genesis 12:6 and Deuteronomy 11:30). In the other passages (Genesis 13:8, 14:13, 18:1) it has חזוי, חיזוי, meaning a lookout or crossroad.[7] In any event, like Onkelos, the Targum Yerushalmi avoids referring to a tree.

- The Septuagint, on the other hand, consistently translates our passages with the term drus, a tree or oak tree, which in two passages (Genesis 12:6 and Deuteronomy 11:30) is referred to as “high” or “tall” (hupselos).

- The Vulgate translates the passages in Genesis with the term convallis, a valley, but in Deuteronomy 11:30 employs the terms valles, valley, and campester, flat or level country. In these passages, then, the Vulgate is far closer to Onkelos than to the Septuagint.

In conclusion, there is no agreement among the ancient versions. Some (Samaritan, Peshitta, Septuagint) consistently follow the Hebrew eilon, eilonei as referring to a tree or trees. Others (Sa`adiah’s Tafsir, Targum Yerushalmi, and the Vulgate) use various geographic terms indicating a plain, valley, lowland, meadow, crossroad, etc., all of which are similar in general meaning to meishar in Onkelos. Whether this usage reflects either familiarity with Onkelos or a concern to avoid pagan connotations, as has been suggested for Onkelos, is a matter of conjecture.