Walks About the City and Environs of Jerusalem

Title Page; Illustration: Jewish Family on Mount Zion

Biographical background

The British artist William Henry Bartlett was born in London in 1809, and became famous for his many drawings of his travels throughout Britain, the Balkans, North America, and the Middle East. His sepia wash drawings of sites he visited were made in the exact size of the steel engravings made from those drawings and published in his books.

Self-Portrait of William Henry Bartlett

In 1854, Bartlett became suddenly ill while returning to Britain from his last trip to the Near East on the French steamer “Egyptus” and died off the coast of Malta on 13 September 1854 at the age of 45.

The Morning Chronicle (London) 27 September 1854

The Caledonian Mercury (Edinburgh, Scotland), 2 October 1854

Walks About the City and Environs of Jerusalem: Bartlett’s Critical Approach

Bartlett’s Walks About the City and Environs of Jerusalem records and illustrates his studies and impressions of Jerusalem on a visit in the summer of 1842. The book was originally published in 1844,[1] with a second edition a few years later.[2]

An affirming Anglican Christian, Bartlett refers the reader at various points to associations of sites he visited and drew with passages in the Bible (the Jewish Scriptures and the New Testament), occasionally cites descriptions of sites in the histories of Josephus, and frequently refers to the recent and detailed studies of the American biblical scholar Edward Robinson (1794-1863), often regarded as a founder of biblical archeology.[3]

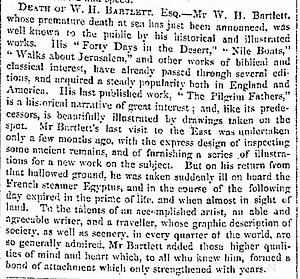

South-West Corner of Temple Mount – Robinson’s Arch

The fact that many of Bartlett’s conclusions and speculations – like those of Robinson – have since been revised and/or disproven by subsequent archeological research in Jerusalem (especially since the reunification of the city in 1967) in no way detracts from the magnificence of his intellectual efforts to understand the history, topography and geography of the city, and from the beauty of his illustrations, which have historical as well as artistic value. As the saying goes, a dwarf standing on the shoulders of a giant will see farther than the giant, and the conclusions and speculations of today’s research are also likely be revised and/or disproven by future research.[4]

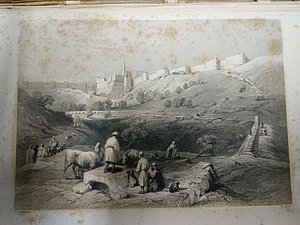

Jerusalem from the east – from the Mount of Olives

Bartlett’s approach to studying Jerusalem, and attempting (like Robinson) to determine the precise location of sites of historical and religious importance, combined a critical respect for evidence – physical, topographical, geographical as well as literary – with his Anglican Christian religious beliefs. He frequently expressed his grave doubts concerning many “traditional” religious claims, often dismissed by him as “monkish tradition” and even “fraud.”

Here is an example of Bartlett’s combination of religious appreciation with critical study:

If there be holy ground on earth, it is here. Nor is there anything to disturb the full impression of identity, which at once passes into the mind, with the scene of so many wonderful and touching events. We are neither confused with learned theories, nor repelled by the palpable inventions of pious fraud.[5]

Jerusalem from the West with David’s Citadel

Front: Dam of Sultan’s Pool in Valley of Hinom (Gehinom; Gehenna)

(On the far right is the hill called “Mount Zion” by early Christian pilgrims)

In his description of what is traditionally believed to be King David’s Tomb on the south-western hill (just outside the current city walls) called “Mount Zion”[6] ever since it was so identified by early Christian pilgrims, a complex which also contains the “Cenacle” associated with the “upper room” of the “Last Supper,”[7] Bartlett commented:

The group of buildings . . . where various events of the life of Jesus have been placed by tradition, without the shadow even of probability.[8]

Upon descending the Via Dolorosa, he wrote:[9]

The descent is by a steep and rugged street, called the “Via Dolorosa,” from the monkish tradition, that Jesus, laden with the cross, ascended it.

At the traditional location of Jesus’ passion, Bartlett expressed his doubts as to the historicity of that site, at the base of the Mount of Olives,[10] as well as of sites higher up on the Mount (where there are now the churches of Dominus Flevit on the side, and of the Ascension on the Mount’s peak).

Here tradition has given the name of the Garden of Gethsemane to a group of ancient olives, in the depth of the glen, and has also pretended to identify the scene of the ascension, and of the prophecy of the ruin of Jerusalem.[11]

Little could Bartlett foresee the continuing excavations of the City of David (on the ridge to the south of the Temple Mount) in our day, which have exposed remnants of the original city going back to the time of David and the Jebusites:

We need hardly say, that there can be no remains of what was once the city of David. Monkish traditions, indeed, pretend to point out some, but they are wholly destitute of foundation.[12]

To reiterate: the point is not that we know more than Bartlett, but that this early student of the history of Jerusalem was suspicious of religious claims lacking the scientific, physical (as well as ancient literary) evidence from which our generation has benefited, thanks to modern archeological research, nearly two centuries later.

The State of Jerusalem in Bartlett’s Day

Bartlett’s own observations and illustrations, based on his extensive and careful field explorations, whatever their accuracy (in light of more recent discoveries) regarding ancient sites, are also important for understanding the state of Jerusalem in his day, as the city was prior to much subsequent building which often obscured or obliterated older strata, and also for his descriptions of the Jewish, Muslim and Christian inhabitants prior to massive immigration and the expansion of the city outside the Old City walls in later generations. Moreover, his illustrations show no buildings outside the walls.

Describing the extreme poverty of Jerusalem and especially its Jewish inhabitants in his day, Bartlett wrote:[13]

If the traveler can forget that he is treading on the grave of a people from whom his own religion has sprung, on the dust of her kings, prophets, and holy men, there is certainly no city in the world that he will sooner wish to leave than Jerusalem. Nothing can be more void of interest than her gloomy, half-ruinous streets and poverty-stricken bazaars, which, except at the period of the pilgrimage at Easter, present no signs of life or study of character to the observer . . . Jerusalem. . . no longer the capital of a nation, and remote from the centre of traffic, is destitute of any interest but that connected with the past; and the traveler gladly hastens from the dullness and misery within her walls, to the lonely hills around, where there is nothing to disturb the picture of the momentous events brought before him by his imagination.

Jerusalem from North-East (from the then “lonely hill” of Mount Scopus)

By contrast, in an appendix describing his visit to Hebron and the tombs of the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and the matriarchs Sarah, Rebecca, and Leah, he wrote:[14]

These associations of the patriarchal age, were to us most deeply interesting, on the spot and amidst the people to whose ancestors they refer. And if we might judge by the fine faces we saw around us, they have in no respect changed but in circumstances, unlike other conquered people. They are generally in better plight here than at Jerusalem, or their other holy places in Palestine.

En route to Hebron, Bartlett drew what has for some centuries been believed to be the tomb of Rachel:[15]

Tomb of Rachel

In Bethlehem, Bartlett was hosted by the Greek Orthodox Bishop at the Church of the Nativity. While appreciating the hospitality, Bartlett noted:[16]

The good father could not but know that he was honouring and feasting . . . another ecclesiastical rival, only to be treated with more courtesy than the detested Latins, as being under the powerful patronage of England.

The rivalry, however, was not limited to Greek Orthodox –Roman Catholic relations, and was also observed by Bartlett in the tensions, inter alia, between Christian Bethlehem and Muslim Hebron:[17]

The Bethlehemites would appear to be a people of remarkable capacity, and withal, of a restless ungovernable temper, with difficulty kept in order, even by their spiritual guides, and breaking out, when the pressure of a high-handed tyranny is at all withdrawn, into bloody feuds with their neighbors, especially the Hebronites, as did formerly the clans of Scotland and Ireland. This state of things will necessarily exist till the establishment of an enlightened government, of which, however, we cannot see the remotest chance for Palestine, with its many races and creeds, and their ancient and deeply-rooted antipathies and conflicting interests.

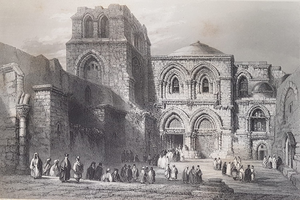

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

An obvious question for Bartlett to examine was the site of Golgotha (Calvary). As is well known, the problem was that the location and outline of the Second Wall in the time of Jesus could not (and cannot) be precisely determined, because the area is built-up and cannot be excavated. If the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is within that wall, it cannot have been the site of a tomb, since burials had to be located outside the city walls. Although we still do not know exactly where the Second Wall stood in that area, recent excavations beneath the adjacent Lutheran “Erlöserkirche” (“Church of the Redeemer”), which was inaugurated in 1898 in the presence of Kaiser Wilhelm II, have exposed findings from that period, thereby giving significant historical support to the tradition that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is located outside the Second Wall and does, indeed, mark the spot of Golgotha.

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Bartlett, however, did not have the benefit of these recent excavations. Nevertheless, in the absence of physical evidence, his speculations were reasonable:

The question of the identity of the site of Calvary with the present Sepulchre, is involved in much historical and topographical obscurity. We cannot indeed doubt that the apostles and first Christian converts at Jerusalem, must not only have known the spot, but that this knowledge must have descended to the next generation, even though no particular sanctity were by them attributed to it. . . Making every allowance for the fact that the first converts were rather absorbed in the spiritual influences of Christianity, than careful about the different sites of its history, we think it must still be conceded, that it is very improbable that the knowledge of those lying immediately around them should entirely die out. The presumption, then, would seem reasonable, that the Christians at Jerusalem must have been acquainted with the real Calvary, when Constantine erected the original church of the Holy Sepulchre upon the same site by that now standing.[18]

On the other hand, the physical location of Golgotha aside, Bartlett could not accept much of what has been sanctified by tradition within the Holy Sepulchre:

Within the vestibule, the first object is a slab of marble, upon which it is said the body of Jesus was laid, after the crucifixion, to be anointed, before it was committed to the tomb. This and other palpable absurdities would tend, even were our convictions as to the site of the Sepulchre itself quite settled, to disgust and repel us, and weaken the impression with which we might otherwise regard it.[19]

While firmly dismissing these “invented or imagined” traditions, and the behavior of pilgrims to the church, Bartlett acknowledged the emotional power of those “ignorant” pilgrims’ beliefs:

The centre of attraction to the devoted but ignorant multitude is, of course, the Church of the Sepulchre; and marshalled by their respective religious guides, they rush with frantic eagerness to its portal, and in this excited state visit the many stations invented or imagined in credulous ages. The whole scene of Christ’s crucifixion and entombment are brought before the eye with such vividness, that even Protestants who came to scoff, have hardly been able to resist the contagious effect of sympathy with the weeping pilgrims.[20]

Therefore, despite his clear rejection of the religious traditions regarding the Holy Sepulchre, Bartlett could still regard the place as “holy ground” – not because the pilgrims’ “superstitious feelings” were factually true, but because of the deep piety and personal dedication of the pilgrims who believed those traditions:

Though we cannot be affected by the Holy Sepulchre, as others may, yet when we think of the thousands who have made this spot the centre of their hopes, and in a spirit of piety, though not untinctured with the superstitious feelings of bygone ages, have endured danger, and toil, and fever, and want, to kneel with bursting hearts upon the sacred rock; then, as regards the history of humanity, we feel that it is holy ground.[21]

Criticism of Inter-Christian Rivalry and Animosity

However, Bartlett’s harshest criticism – to the point of disgust (the term he used in the passage cited above) – was aimed at the rivalries and animosity among the several Christian denominations he witnessed, reaching their peak during the Easter season at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the ceremony of “Holy Fire” (or “Holy Light” – Hagia Phos) on “Great and Holy Saturday,” the day before the Orthodox Easter.[22]

After citing at length and in small print[23] an anonymous article in “The New Monthly Magazine” describing the “Holy Fire” ceremony in the Holy Sepulchre, Bartlett concluded:

Such are the scenes which pass in this church; disgraceful to the very name of Christianity, and a standing argument against its truth, in the minds of both Turks and Jews.[24]/p>

Criticism of Millennial Hopes for the Conversion of the Jews

In a similar vein, Bartlett was critical of millennial Christian hopes for the conversion of the Jews, in no small measure because of “corrupt and superstitious forms of Christianity existing in Jerusalem,” but also because the suffering of the Jews reinforces their “stubborn prejudices,” and at the same time their fidelity and hopes for their future:

The hoped for conversion of the Jews has, for some time past, given rise to great activity among various bodies of Christians in England, some of home, from their peculiar mode of interpreting prophesy, are in expectation of the speedy advent of the Millennium, and of the literal restoration of the Jews to the land of their forefathers . . . Humanly speaking, Jerusalem is the last place where we may expect to meet with converts, where every object tends to keep alive among the Jews the spirit of their religion – the sacred hills, the cemeteries of their fathers, the walls of their once proud temple. Even their very distress and degradation must powerfully contribute to fix their minds on the holy books, which foretell their future glory, when the measure of their suffering shall be fulfilled. The influence of corrupt and superstitious forms of Christianity existing in Jerusalem, in fortifying the contempt of the Mussulmen, has often been noticed, nor is it less fatal in its effect upon the Jews; perhaps a purer form of religion, substituting practical benevolence for angry denunciation, might have some effect in softening the stubborn prejudices which have gathered strength from the oppressions of past ages.[25]

Bartlett then added the following note:[26]

NOTE: “You wish to convert us to Christianity,” said a Jew to Mr. Wolff; “look to Mount Calvary, where Jesus of Nazareth was crucified, of whom you say that he came to establish peace on earth. Look to Calvary, there his followers reside – Armenians, Copts, Greeks, Abyssinians, and Latins; all bear the name of Christians, and Christians are shedding the blood of Christians on the same spot where Jesus of Nazareth died.”

In conclusion, today’s readers of Bartlett’s book, especially those of us, Jews, Christians, and Muslims, who live in and love Jerusalem in the generation of “the literal restoration of the Jews to the land of their forefathers,” can not only profit with enjoyment from his scholarly speculations, beautiful illustrations, and vivid descriptions of the land, the city, and its inhabitants some 175 years ago, but also can consider to what extent in the interim we have all progressed in facing the challenge he posed in the passage already cited:[27]

This state of things will necessarily exist till the establishment of an enlightened government, of which, however, we cannot see the remotest chance for Palestine, with its many races and creeds, and their ancient and deeply-rooted antipathies and conflicting interests.