The language of guilt is built around two metaphors that articulate the condition of being guilty as either a pollution, stain, or defilement that must be purified, or as a weight and burden that can be transferred, lifted, born, and carried away. These metaphors are universal and rooted in our bodies. All of the world’s religions offer rituals of purification to alleviate the weight and stain of trespasses against the sacred order and moral boundaries of communities.[2] Traditional religious rituals of purification use water (e.g., baptism, Mikveh, Ganges river), blood (e.g., animal sacrifices, Eucharist), fire and smoke (e.g., fire sacrifice, smudge sticks, sweat lodge) to remove impurities caused by transgressions against the sacred order. Purification rituals provide the procedures by which the symbolic and sacred order is renewed and recreated after violations against God and neighbor. The correlation of washing and spiritual or moral purification is well established in the history of religions, including Christianity. Social psychologists have recently retested this hypothesis and found that secular contemporaries feel physically dirty when they are reminded of moral wrongdoing. Called the Macbeth Effect after Shakespeare’s gripping portrait of Lady Macbeth’s obsessive attempts to wash off the blood of guilt, several studies have confirmed a correlation between a perceived need for physical cleansing and the memory of moral wrongdoing.[3]

Both the New Testament and the Hebrew Bible use imagery of pollution and defilement that must be purified. Water and sacrificial blood are the preferred methods of purification. The New Testament interprets the passion of Christ as a purifying sacrifice, his blood cleanses sin and guilt. So, for instance Hebrews: “if the blood of goats and bulls, with the sprinkling of the ashes of a heifer, sanctifies those who have been defiled so that their flesh is purified, how much more will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without blemish to God, purify our conscience from dead works to worship the living God” (Heb 9:13-14)! Christ’s blood washes away sins and he dies so that “that he might redeem us from all iniquity and purify for himself a people of his own who are zealous for good deeds” (Titus 2:14). In baptism, “you were washed, you were sanctified, you were justified” (1 Cor 6:11) and in the eucharist, the “blood of Jesus Christ his Son cleanses us from all sin” (1 John 1:7). Sacrificial blood and sacred water are universal detergents to cleanse spiritual and social violations of the social and symbolic order.

In the Hebrew Bible, trespasses against God’s divine ordinances must be expiated by rituals of purification, often involving the entire community. Unless the culprit is punished, the entire community is implicated in guilt by association, which pollutes the land, undermines social cohesion, and obstructs relations with God:

You shall not pollute the land in which you live; for the blood pollutes the land, and no expiation can be made for the land, for the blood that is shed in it, except by the blood of the one who shed it. You shall not defile the land in which you live, in which I dwell; for I the LORD dwell among the Israelites<(Num 35:33-34).

On the Biblical paradigm, it is the entire community that is implicated and under obligation to respond, prosecute, and punish the culprit. Only some people in a community are guilty but all are responsible. Until the community vindicates the victims by imposing the rule of law, the pollution of moral violation spreads. While this may sound like ancient tribal blood feud customs, this imagery is regaining relevance in contemporary discussions of political crime and atrocities.<a data-cke-saved-name=">[4] The Holocaust, for instance, implicated everyone who was not circumcised or a member of the Jewish community. Complicity is a form of pollution, silence and indifference are signs of collusion.

Guilt as Weight and Burden

The second metaphor for guilt involves weights and burdens that must be born or can be lifted. The scapegoat ritual is the most prominent text that suggests that the sins of the community are transferred and carried into the desert in order to rid individuals and the community of personal and communal guilt:

Then Aaron shall lay both his hands on the head of the live goat, and confess over it all the iniquities of the people of Israel, and all their transgressions, all their sins, putting them on the head of the goat, and sending it away into the wilderness by means of someone designated for the task. The goat shall bear on itself all their iniquities to a barren region; and the goat shall be set free in the wilderness (Lev 16:20-22).

This ritual visualizes sin and guilt as a burden that can be loaded and eased. It is from this process of garbage removal that we also derive the associative field of Gehenna, the Hebrew word for hell, which, some have argued, refers to the garbage dump outside of the walls of Jerusalem, where smoldering flames slowly consumed the stinking detritus of human consumption. Garbage disappears by common design, we no longer perceive and acknowledge its existence. But in reality, it has not vanished, even though it has lost its value and right to exist. That which has been thrown away smolders and stinks in fiery pits and foul landfills.

Christ as sacrificial scapegoat carries away the weight of iniquity and disposes humanity’s sins in some remote corner of the universe. Is that how reconciliation can work? What happens to the remainders of guilt? We must question this imagery on ecological, moral, and spiritual grounds, and consider the possibility of toxic super fund sites in the realm of historical evil. Guilt may not disappear down hidden drainage pipes and or on the backs of waste management scapegoats, but require intentional bioremediation and composting.

The history of Christian anti-Judaism is a case in point. Before the Holocaust, anti-Judaism established and sustained Christian triumphalism, but after the murder of six million Jews in the heart of European Christendom, the teaching of contempt became a liability. The Holocaust made Christian anti-Judaism odious. But although many church bodies rushed to declare antisemitism a “sin against God” (WCC 1948) and “denial of the spirit and teaching of our Lord (WCC 1946), anti-semitism’s role and function, shape and history, remained obscure, unknown, and vague. The question of guilt is instructive here.

Whose Guilt Is It Anyway?

From the start, many Christians, and certainly the Nazis, blamed Jews and Judaism for all of the misfortune in the world. Anti-Judaism is built upon the charge of the murder of Christ, a charge that looms large and extends into supposedly secular antisemitic propaganda. Anti-Jewish tropes picture Jews as persecutors of Christ, who entrap the innocent and corrupt the Christian world. Because the Jews called the blood of Christ upon their own heads, whatever legal, political, and physical violence came their way was deserved. God himself, according to this teaching, rejected and punished this people. This collective guilt spreads to the entire people of Israel, living then and there, or here and now. Punishing the Jews became a righteous and Christian duty. Der Stürmer, a crude and pornographic anti-Semitic propaganda publication of the Nazi party, routinely ran caricatures of the Cross to convey its message that “the Jews are our misfortune (Unglück).” A looming Jewish face watches the crucifixion of an Aryan-looking Christ (figure 1), and in one case, of a naked female figure, “Ecce Germania.”[5] As Christ-Killers, the Jews also threaten the survival and well-being of Germania. Despite their pretense of scientific racism, Nazi antisemitism used the Christian trope of collective guilt for the conspirational entrapment of the Son of God to authorize violence against the Jews. This allowed Nazi authorities to recruit willing collaborators from among German, Austrian, Polish, Ukrainian, French, and Dutch Christians. The Final Solution, on that view, completed the rejection by God Himself, who condemned this people into exile. Contrary to the WCC’s claim that antisemitism was in “denial of the spirit and teaching of our Lord” (WCC 1946), the Christian story was routinely used to mobilize antisemitic violence.

Figure 1. Front page of Der Stürmer, January 1939

This projection of guilt was at the heart of the Christian Teaching of Contempt, and constituted, as Rosemary Radford Ruether put it, “the left hand of Christology.”[6] The guilt of the Jews was hammered home in sermons and sculpture, art and architecture, scholarly treatises, and popular pamphlets: Jews were guilty of killing Christ, guilty of persecuting the prophets, guilty of disobedience, guilty of blindness, guilty of arrogance, and guilty of refusing to fade into oblivion. Israel was cursed for its guilt, deprived of its covenant, banished from its land, dispersed into exile, and condemned to abjection at the hands of the Church, the New Israel.[7]

As much as the Christian churches needed and wanted to disassociate from the genocidal violence of the Holocaust, they were not immediately ready to renounce Jewish guilt. Consider the Declaration on Jewish Question issued by the Council of Pastors of the Confessing Church (Reichsbruderrat) in 1948. This statement was supposed to redress the silence about the Holocaust in the original “Declaration of Guilt” in Stuttgart in October of 1945. The 1948 declaration affirms the Jewishness of Jesus, and repudiates singular guilt attributions to the Jews for his death. But in the second and fifth point, the declaration reiterates Israel’s supposed rejection of its vocation and God’s punishment of the people of Israel as a warning and exhortation for the New Israel, the Church:

(2) In crucifying the Messiah, Israel has rejected its election and vocation. All of humankind has repudiated the Christ of God in this event. We are all co-guilty for the crucifixion of Christ. Therefore, the church is not allowed to stigmatize the Jews as solely guilty for the cross of Christ… (5) Standing under the judgment of God, Israel confirms the irrefutable truth and reality of the word of God, to the continuous admonition of his church. That God cannot be mocked is the silent sermon of the Jewish fate, as a warning to us and as an exhortation to the Jews to consider conversion to the One, in whom alone rests their salvation.[8]

Three years after the military defeat of Nazism, representatives of the Confessing Church, who had split from the state-controlled German Evangelical Church over the Aryan Paragraph, could not stop blaming the Jews for their own misfortune. At their meeting in 1948, they continued to hold the Jews accountable for their own punishment as a natural consequence of their rejection of Christ. This position remained ascendant long into the 1960s, when Jewish theologian Richard Rubenstein encountered it in his visits with German church representatives, including those who were arguably sympathetic to Jews, such as Dean Heinrich Grüber, who had run the church relief office in Berlin during the war for non-Aryan Christians and Jews, called the “Pastor Grüber Bureau.” Grüber was as “woke” as any German clergyman at the time and traveled to Jerusalem as the only German to testify against Adolf Eichmann. But in his conversations with Richard Rubenstein, he also interpreted Jewish suffering through the lens of divine punishment for the betrayal and rejection of Christ. For Rubenstein, such theological meaning-making proved that antisemitism was deeply ingrained in the mythic structure of Christianity itself:

Even when Christians assert that all men are guilty of the death of the Christ, they are asserting a guilt more hideous than any known in any other religion, the murder of the Lord of Heaven and Earth...The best that Christians can do for the Jews is to spread the guilt, while always reserving the possibility of throwing it back entirely upon the Jews. There is no solution for the Jews…[9]

The discussions and eventual renunciation of the “deicide charge” occurred over the course of the 1960s. The first church to disavow the deicide charge as a “tragic misunderstanding” was House of Bishops of the Episcopal Church in the USA in 1964.[10] Their statement explains: “To be sure, Jesus was crucified by some soldiers at the instigation of some Jews. But this cannot be construed as imputing corporate guilt to every Jew in Jesus’ day, much less the Jewish people in subsequent generations.”[11] A year later, in 1965, Nostra Aetate, widely acclaimed as the moment of “sea change” in Jewish-Christian relations, was passed overwhelmingly by the Second Vatican Council in Rome:

True, the Jewish authorities and those who followed their lead pressed for the death of Christ; still what happened in His passion cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews today. Although the Church is the new people of God, the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scriptures.[12]

The attribution of Jewish guilt is the corner stone on which the election of the Gentile Christian church was built. It establishes the reason for God’s rejection and replacement of the people of Israel. It grounds Jewish abjection and exile. For all of its irrationality, it took enormous internal theological debate and political pressure to renounce the idea that every Jew, at every point in history and everywhere, could be held personally accountable for the death of Christ. Without retributive reasoning, Christian contempt and violence loses a key argument. If God has no reason to punish the Jews, then Christians lose the reason to curse and consign Jews to hell. The official retraction of Jewish guilt allowed the churches to consider the theological integrity and religious vitality of rabbinic Judaism. Only then did the churches recognize the infliction of suffering on Jews as culpable history.

The Purification of Memory

When Pope John Paul II spoke of the “purification of memory” to guide the millennial celebrations in the Jubilee year 2000, he invited the Church to come to terms with culpable histories, including the crusades, the Inquisition, the slave trade, colonialism, and the Holocaust.[13] When Pope John Paul II prepared the Church for the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000 in his Apostolic Letter Tertio Millennio Adveniente (1994), he introduced the concept of the purification of memory:

She [the Church] cannot cross the threshold of the new millennium without encouraging her children to purify themselves, through repentance, of past errors and instances of infidelity, inconsistency, and slowness to act. Acknowledging the weaknesses of the past is an act of honesty and courage which helps us to strengthen our faith, which alerts us to face today's temptations and challenges and prepares us to meet them.[14]

This concept was reiterated in subsequent documents, such as the Bull Incarnationis Mysterium (1998), which similarly wrestled with “the weariness which the burden of two thousand years of history could bring with it” and affirmed:

“First of all, the sign of the purification of memory; this calls everyone to make an act of courage and humility in recognizing the wrongs done by those who have borne or bear the name of Christian. ... Because of the bond which unites us to one another in the Mystical Body, all of us, though not personally responsible and without encroaching on the judgment of God who alone knows every heart, bear the burden of the errors and faults of those who have gone before us. Yet we too, sons and daughters of the Church, have sinned and have hindered the Bride of Christ from shining forth in all her beauty.”[15]

Purification is key to renewal, evocatively expressed in the image of the young, virginal, untouched bride. This image of purity is problematic not only for its sexual politics but also for its implicit erasure of the old. The call to “clean house” and purify the church all too often means “whitewashing” or, worse, “sweeping the dirt under the rug.” Metaphors of composting, on the other hand, affirm the messy materiality of the past and enrich the existing imagery of washing and waste removal. Composting the remainders of wrongdoing requires patience and strategic engagement. The etymology of the word is derived from the Latin compositum (later compostum) which the OED defines as “(a) composition, combination, compound, (b) literary composition, compendium, as well as (c) a mixture of various ingredients for fertilizing or enriching land, a prepared manure or mould.”[16] It is the exact opposite of purity, which is defined as “the state or quality of being free from extraneous or foreign elements, or from outside influence; the state of being unadulterated or refined.” Purity is white and clear, immaculate and untouched, while compost is rich, dark, smelly, and blended. We do not emerge from guilt untouched and clean but rather richer, deeper, darker beings. Our dirt does not disappear, but enriches the ground that can bring forth new life. It is comparable to the dark chaos that grounds God’s creativity, along the lines of Catherine Keller’s reading of Genesis’ tehom in her book Face of the Deep. As Keller affirms, “rather than marching forward and abandoning the traditions that have failed us (and which have not?) we recycle. We generate new ones from the debris.”[17]

The old is never innocent, and that is as true for individuals as for religious heritages and national histories. Age, inevitably, accumulates breakage and malfunction, failure and debris. By envisioning purity in the image of the Virgin, the untouched bride, “dressed in a simple robe of white linen, the finest linen, bright and pure,”[18] we devalue processes of maturation and ripening. By contrast, symbols such as fermented wine or leavened bread could be used to envision a purity that is inclusive of fermentation, ripening, and transformation. Wine gets better with age. Sour dough transforms bland flour into flavorful bread. Using metaphors of purity derived from fermentation endorses the digestion of the old, broken, discarded, and guilty into something richer and more complex. The purity of compost is complex and diverse. Its goal is not the total complete destruction, absorption, and integration of difference and otherness. The fermentation of shameful remainders creates useable histories.

The revolution proclaimed by Nostra Aetate rested on the deliberate denial of centuries of Christian anti-Jewish teachings. Nostra Aetate did not mention the history of Christian anti-Jewish persecutions nor the churches’ silence and complicity in the Holocaust.[19] It proposed two pathways to move beyond violence and contempt in the past, both of which are problematic because they erase memory. In paragraph 3, which aims to reset the relationship between the Church and Islam, the document calls on both parties to forget:

Since in the course of centuries not a few quarrels and hostilities have arisen between Christians and Moslems, this sacred synod urges all to forget the past and to work sincerely for mutual understanding. On behalf of all, let them together preserve and promote social justice, moral values, peace, and freedom.[20]

The text, by not naming specific “quarrels and hostilities” obfuscates political accountability and moral agency. Quarrels and hostilities break out seemingly without agents. Such language conceals the ideas and institutions that exert power and act strategically to influence and control communities. Without critical analysis of history, the call to forget serves to suppress memories of theological and political conflict that demand critical reflection and institutional change to enable reconciliation after violence.

Paragraph 4 recasts the relationship between the Church and Israel and invokes a very different memorial strategy. Here (in 4.2) the reader is repeatedly exhorted to remember:

the Church…remembers the bond that spiritually ties the people of the New Covenant to Abraham's stock. …The Church, therefore, cannot forget that she received the revelation of the Old Testament through the people with whom God…concluded the Ancient Covenant. Nor can she forget that she draws sustenance from the root of that well-cultivated olive tree onto which have been grafted the wild shoots, the Gentiles. …The Church keeps ever in mind the words of the Apostle about his kinsmen. …She also recalls that the Apostles...[21]

Who decides which memories are to be invoked and which ones are to be overlooked? Numerous commentators have noted that paragraph 4 makes no reference to the Shoah or to centuries of anti-Jewish violence across European Christendom.[22] Furthermore, the text glosses over centuries of Church teachings on the Jews. It is remarkable, as John Pawlikowski pointed out, that the Council disregarded the entire dogmatic body of Church doctrine and instead chose to justify the renewal of the relationship with the Synagogue on a radical return to the Pauline roots:

Examining chapter four of Nostra Aetate we find scarcely any reference to the usual sources cited in conciliar documents: the Church Fathers, papal statements and previous conciliar documents. Rather, the Declaration returns to Romans 9 -11, as if to say that the Church is now taking up where Paul left off in his insistence that Jews remain part of the covenant after the Resurrection despite the theological ambiguity involved in such a statement. Without saying it so explicitly, the 2,221 Council members who voted for Nostra Aetate were in fact stating that everything that had been said about the Christian-Jewish relationship since Paul moved in a direction they could no longer support. . . . Given the interpretive role of a Church Council in the Catholic tradition this omission is theologically significant. It indicates that the Council Fathers judged these texts as a theologically inappropriate resource for thinking about the relationship between Christianity and Judaism today.[23]

Nostra Aetate cleans the slate by sweeping centuries of supersessionist doctrine, liturgy, law, and art under the rug. For selective memory to shift attention to elements of the tradition that express new insight while deemphasizing others that conflict with renewal is certainly legitimate. But what happens to the elements that have been repudiated and excised? Can we simply wipe away the metaphorical dirt of wrong-doing and wrong-teaching by declaring, as Nostra Aetate did, that “no foundation therefore remains for any theory or practice that leads to discrimination between man and man or people and people”?[24] Strategic silence not only fails the victims of ideologies of contempt, whose suffering remains unacknowledged, but also the perpetrators, whose faith must be transformed. Unless the refuse created by a theological revolution such as Nostra Aetate receives further treatment, the uncanny threatens to return.[25]

Rituals of Purification as Clarification

Contrition occurs when a changed perspective meets factual knowledge. Dialogue creates relationships of trust and respect, while learning produces insight that compels revision of stereotypes and recognition of misrepresentations. The more Christians engaged in dialogue with Jews, the more they learned about Jewish religious teachings and the conditions of life under Christian rule. Antisemitism is generally imperceptible to its beholders, because it is hard to distinguish fact from fiction, distortion from accurate representation, defamation from truth. Discernment of one’s own limitations requires external perspectives. Only in meeting the Other do we perceive Ourselves. Maybe for the first time in Christian history, Christians were willing to listen to Jews, learn from Jews, and accept criticism by Jews.[26] The best scholarship on the history of antisemitism in general, and on anti-Judaism in Christian history in particular is often conducted by Jewish historians, sociologists, psychologists, etc. As long as Christian theologians, exegetes, and historians are not willing to listen and learn, engage and absorb this body of knowledge, they feel little urgency to engage in self-critical analysis of the scriptural, doctrinal, liturgical, and cultural traditions of Christianity. It is not enough to express abhorrence at antisemitism; its meaning and impact on Jews and Christians throughout history must be studied.

What then shall be done with the shameful remainders of anti-Judaism, such as Martin Luther’s crude and vulgar anti-Jewish rhetoric, especially his late tractate On the Jews of Their Lies (1543). Is it to be considered marginal and secondary to his theological genius, or central to his theology in its crudity and vulgarity? Most Christians are unaware of his words, which cannot fail to shock, especially in the post-Holocaust world. How do we deal with this disturbing mixture of exquisite theological truth and abhorrent hate speech? Martin Luther does not stand alone, as there are other respected church fathers, medieval mystics, and church leaders who penned vile texts and vicious caricatures, as historians Robert Chazan and David Nirenberg have shown in distressing detail.[27] Can we simply excise the passages and traditions that denigrate, degrade, and dehumanize the Jews? How seriously must we take Martin Luther, when he advises German authorities:

First to set fire to their synagogues or schools and to bury and cover with dirt whatever will not burn, so that no man will ever again see a stone or cinder of them… Second, I advise that their houses also be razed and destroyed… Third, I advise that all their prayer books and Talmudic writings…be taken from them… Fourth, I advise that their rabbis be forbidden to teach henceforth on pain of loss of life and limb… I wish and I ask that our rulers who have Jewish subjects exercise a sharp mercy towards these wretched people… They must act like a good physician who, when gangrene sets in, proceeds without mercy to cut, saw, and burn flesh, veins, bone, and marrow…deal harshly with them, as Moses did in the wilderness, slaying three thousand, lest the whole people perish.[28]

These words were cited and celebrated on November 9, 1938, when 267 synagogues burned across German lands, 7,500 Jewish businesses were looted, 91 Jews were killed, and 90,000 Jews were arrested, interned or deported, while Jewish cemeteries, hospitals, schools, and homes were vandalized. The following day, on November 10, 1938, Wittenberg marked the 455th birthday of Martin Luther with a parade that passed by the destroyed synagogue. And on November 15, 1938, the Bishop of Thuringia, Martin Sasse distributed a reprint of Luther’s text under the revised title: “On the Jews: Away With Them.”[29] In the foreword, he wrote: “On November 10, the birthday of Martin Luther, the synagogues in Germany are burning. In response to the murder of the diplomat von Rath by Jewish hands, the economic power of the Jews is finally broken which crowns the fight for the liberation of our people, which is blessed by God.”[30] Such direct historical continuity between theological history and political reality, between verbal and physical violence, is especially appalling. Not everyone agreed, but what sermons did Roman Catholic and Reformed Christians listen to when they went to church on the Sunday after the pogrom?[31] We know that some Protestant ministers and Catholic priests were arrested by the Gestapo for condemning the violence and preaching solidarity with the synagogue.[32] But the vast majority chose to remain silent, and their silence became assent and acceptance of the violent purge of the German Christian nation.

After the defeat of Hitlergermany, the Christian churches were eager to distance themselves from the violence by emphasizing the secular nature of antisemitism and Nazism. Even the inaugural meeting of the ICCJ (International Council of Christians and Jews) convened as an Emergency Meeting on Antisemitism in Seelisberg, Switzerland in 1946, skirted the issue of the churches’ complicity:

In spite of the catastrophe which has overtaken both the persecuted and the persecutors, and which has revealed the extent of the Jewish problem in all its alarming gravity and urgency, antisemitism has lost none of its force, but threatens to extend to other regions, to poison the minds of Christians and to involve humanity more and more in grave guilt with disastrous consequences. The Christian churches have indeed always affirmed the anti-Christian character of antisemitism, but it is shocking to discover that two thousand years of preaching the Gospel of Love have not suffice to prevent the manifestation among Christians, in various forms, of hatred and distrust toward the Jews.[33]

While Seelisberg marked the beginning of a change of heart (contritio cordis) for the Christian participants, they were not (yet) prepared to seek, speak, or confront the truth (confessio oris). It is simply not true that the Christian churches have “always affirmed the anti-Christian character of antisemitism.” Wishful thinking bends the facts to conform to desires for moral innocence and flawless integrity. Such desires for moral purity are and must be disrupted by facts, empirical research and historical knowledge. The Christian participants of this ICCJ meeting faced, maybe for the first time in Christian history, a morally empowered and politically energized Jewish counterpart. Some of the Jewish attendees, such as the French historian Jules Isaac, had lost their families in the Holocaust. They were in no mood to coddle the conscience of their Christian partners and used their intellectual acuity and moral authority to compel a more truthful confrontation with the Christian tradition. “Moved by the suffering of the Jewish people” begins the text, and “in the course of frank and cordial collaboration between Jewish and Christian members, both Roman Catholic and Protestant, [the Commission] were (sic) faced with the tragic fact that certain theologically inexact conceptions and certain misleading presentations of the Gospel of love, while essentially opposed to the spirit of Christianity, contribute to the rise of antisemitism.”[34] Jules Isaac was one of the lead authors of the Ten Points of Seelisberg, and he wanted more than vague niceties: “We have the firm hope that they [the Church] will be concerned to show their members how to prevent any animosity towards the Jews which might arise from false, inadequate or mistaken presentations or conceptions of the teaching and preaching of the Christian doctrine, and how on the other hand to promote brotherly love towards the sorely-tried people of the old covenant.”[35] For the first time in Christian history, animosity towards Jews was declared a problem. This point deserves repeating: Before 1945, respectable Christian theologians felt no shame teaching and preaching contempt for the Jewish people and religion. It was only after the Final Solution of the Jewish Question, that rabid denunciation and defamation of Jews and Judaism became problematic and shameful.

The destruction of European Jewry forced Christian theologians and church leaders to consider the role of triumphalism and supersessionism in the genocidal violence unleashed by Nazism. The German churches went first, not least for political reasons. In 1980, the Rhineland Synod unambiguously acknowledged “Christian coresponsibility and guilt for the Holocaust—the defamation, persecution and murder of the Jews in the Third Reich.”[36] Global Lutheranism similarly felt under pressure for its denomination’s national origins and proximity to the land of the perpetrators.[37] Franklin Sherman describes the National Assembly of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in American (ELCA) in 1993, in which the Rev. John Stendahl brought forth a resolution to renounce Luther’s antisemitic writings, which occasioned vigorous debate and resistance, “in which some maintained that such an apology was both unnecessary and unseemly. But when proponents of the measure read out some of Luther’s hateful words, the delegates—most of whom had been completely unaware of this aspect of their heritage—were shocked into voting overwhelmingly for the preparation of such a statement.”[38] The members of the assembly, writes John Stendahl, “seemed stunned to hear such words from Luther. The motion and then the amended resolution both passed with overwhelming support.”[39] As Alana Vincent points out in her analysis of Jewish-Christian statements on the Holocaust, Lutheran churches across the globe were particularly sensitive to guilt by association.[40] Two years later, in the spring of 1994, the National Assembly of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of American (ELCA) adopted a resolution that read: “In the spirit of that truth-telling, we who bear his name must with pain acknowledge also Luther’s anti-Judaic diatribes and the violent recommendations of this later writings against the Jews. As did many of Luther’s own companions in the sixteenth century, we reject this violent invective, and yet more do we express our deep and abiding sorrow over its tragic effects on subsequent generations.”[41] Luther’s words, and their direct implication in subsequent political events, made such disavowals unavoidable. For other churches, Anglican, Methodist, Baptist, Roman Catholic, the links were less straightforward. Their statements, Vincent criticizes, merely deplore “the actions of individuals in order to protect the doctrinal positions of the Church,” and “gloss over issues in their own theology by perpetuating the narrative of anti-Semitism as a particularity of Lutheranism.”[42] Christian anti-Judaism is not a peculiar Lutheran theological issue, and antisemitism is not a peculiar German national issue. But Luther’s German nationality made this guilty legacy undeniable.

For ecclesiological reasons, Roman Catholic statements generally avoid explicit guilt confessions since the Church is considered the body of Christ, and therefore intrinsically holy and pure. Only the “sons and daughters of the Church” act in sinful ways and accrue guilt.[43] Hence, “We Remember” (1998) expresses remorse for the Holocaust on behalf of unspecified agents: “The Catholic Church desires to express its deep sorrow for the failures of her sons and daughters in every age.”[44] Compared to Nostra Aetate of 1965, much progress had been made in the way of accepting Christian accountability. But since the purity and integrity of doctrine must be preserved for reasons of ecclesiology, it becomes harder to explicitly name the theological changes that must be enacted in order to confront supersessionism and triumphalism.

Official church proclamations and declarations, whether Catholic or Protestant, are necessary but not sufficient to implement changes to theological language, liturgical practice, and scriptural interpretations. Constructive work of theological reform must follow general statements of condemnation. The overall theological, exegetical, liturgical, and pedagogical narrative of Israel as the people of the “Old Testament,” who were promised but rejected Jesus as the Messiah must change. The Gentile Church has not replaced Carnal Israel. Instead, the emerging story of the Parting of the Way validates post-biblical Rabbinic Judaism as an alternative response to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE, which ended sacrificial worship as mandated in the Torah, and allowed the Jewish community to maintain its devotion to the God of Israel inside and outside of the land of Israel. Instead of rivalry and supersession, the new story values learning in dialogue and difference. The theological recognition of the Jewishness of Jesus creates new theological insights and allows for surprising discernment and discovery.[45] Far from destroying Christianity, repentance invigorates and renews.

But this work has not penetrated all Christian denominations or arrived in all parishes and pews. Far from it, and we would deceive ourselves to assume that supersessionism and anti-Judaism have lost their force. Furthermore, the new media landscape has created new vectors for the distribution of antisemitic traditions. For instance, Martin Luther’s On the Jews and their Lies is readily available on Amazon. Indeed, it is “Recommended” and ranked #5 in “Lutheran Christianity.”[46] “Frequently Bought Together List” with this title are antisemitic canards, such as Henry Ford’s “The International Jew” in four volumes, as well as The Talmud Unmasked. In their “customer reviews,” readers are pleased to receive “forbidden knowledge” that confirms their antisemitic sentiments. Hence, official church statement may no longer have any control over the messages that people choose to embrace.

Repentance is not about repairing the past but about building a different future. This means foremost that Christian theology must adjust itself in such a way that Judaism comes into view as more than Christian prehistory. Without the Synagogue, there is no Christian future. This insight is particularly salient in Germany, where the Jewish community was destroyed and almost all synagogues were burnt to the ground. It was this near-extinction that shocked a segment of the German churches and population into the realization that a Jewish presence is desirable and necessary for theological, political, and cultural reasons.[47] There is no viable Christian future without Jews. Theologically, this is more than mere “philosemitism,” a pejorative term that refers to the smothering embrace by the overbearing religious majority, which is cause for alarm for diasporic minority Jewish communities.

Dresden

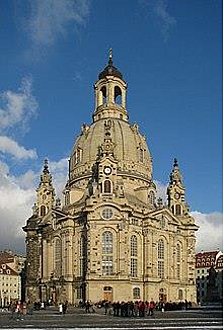

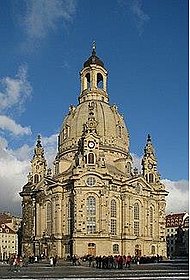

Figure 2. Dresden Frauenkirche | Take the example of Dresden. Shortly after reunification, the people of Dresden organized a movement to rebuild the iconic cathedral of Dresden, known as the Frauenkirche (figure 2).[48] The Frauenkirche had remained a pile of rubble for the duration of the German Democratic Republic, a reminder of the bombing of Dresden that created a fire storm and leveled the city (figure 3).[49] One year after the collapse of the GDR, as a result of grass roots organizing by the non-violent resistance movement that had often met in church basements, the “Call from Dresden” went out asking for international donations to rebuild the church from the rubble. The architectural challenge of separating, cleaning, and reusing 20,000 cubic feet of debris was one thing; the international response to the fundraising appeal, especially from Great Britain whose Royal Airforce had laid waste to Dresden on February 13-14, 1945 was another. Of the 230 million euros needed for the reconstruction, 100 million came from private donations from Germany, Britain, the USA, and other countries. The twoton golden cross was fully paid by the “British people and the house of Windsor” and created by British goldsmith Alan Smith, whose father had flown the mission against Dresden. |

Take the example of Dresden. Shortly after reunification, the people of Dresden organized a movement to rebuild the iconic cathedral of Dresden, known as the Frauenkirche (figure 2).[48] The Frauenkirche had remained a pile of rubble for the duration of the German Democratic Republic, a reminder of the bombing of Dresden that created a fire storm and leveled the city (figure 3).[49] One year after the collapse of the GDR, as a result of grass roots organizing by the non-violent resistance movement that had often met in church basements, the “Call from Dresden” went out asking for international donations to rebuild the church from the rubble. The architectural challenge of separating, cleaning, and reusing 20,000 cubic feet of debris was one thing; the international response to the fundraising appeal, especially from Great Britain whose Royal Airforce had laid waste to Dresden on February 13-14, 1945 was another. Of the 230 million euros needed for the reconstruction, 100 million came from private donations from Germany, Britain, the USA, and other countries. The twoton golden cross was fully paid by the “British people and the house of Windsor” and created by British goldsmith Alan Smith, whose father had flown the mission against Dresden.

Take the example of Dresden. Shortly after reunification, the people of Dresden organized a movement to rebuild the iconic cathedral of Dresden, known as the Frauenkirche (figure 2).[48] The Frauenkirche had remained a pile of rubble for the duration of the German Democratic Republic, a reminder of the bombing of Dresden that created a fire storm and leveled the city (figure 3).[49] One year after the collapse of the GDR, as a result of grass roots organizing by the non-violent resistance movement that had often met in church basements, the “Call from Dresden” went out asking for international donations to rebuild the church from the rubble. The architectural challenge of separating, cleaning, and reusing 20,000 cubic feet of debris was one thing; the international response to the fundraising appeal, especially from Great Britain whose Royal Airforce had laid waste to Dresden on February 13-14, 1945 was another. Of the 230 million euros needed for the reconstruction, 100 million came from private donations from Germany, Britain, the USA, and other countries. The twoton golden cross was fully paid by the “British people and the house of Windsor” and created by British goldsmith Alan Smith, whose father had flown the mission against Dresden.

The reconstruction of the cathedral of Dresden was billed as a project of reconciliation. The pile of stones was cleared in 1994 and by 2005, eleven years later, the cathedral was rededicated in its original splendor.

Figure 3. Frauenkirche ruins and Luther Monument in 1958

But several people on the organizing committee, including the Protestant pastor Siegfried Reimann, tied the reconstruction of the cathedral to the rebuilding of the synagogue. They wanted to link the ruins of the church to the obliteration of the synagogue of Dresden. Built by renowned architect Gottfried Semper in 1840, the synagogue was burnt to the ground on November 9, 1938, its stones dispersed and used for street and infrastructure projects. The Star of David was saved by a brave local fire fighter, who climbed on the roof, took down the star and hid it. The destruction of these two religious houses of worship was connected, and the reconstruction of one made the absence of the other more visible. There was almost no Jewish community left in Dresden. When I visited the Jewish community in Dresden in 1986, we were greeted by a huddle of elderly survivors, who gathered in a barren apartment to serve coffee and cake. This Jewish remnant kept a low profile in East Germany, and had no money to build a synagogue. But the fund raisers for the reconstruction of the church decided to link it with the synagogue. Monies that flowed to one were also dedicated to the other. For instance, the newspaper Die Zeit reported in 1999 that the German American biologist Günther Blobel donated his Nobel prize money to the fund to rebuild Frauenkirche as well as the synagogue.[50]

While the reconstruction of the church cost 250 million Euros, the construction of the synagogue cost a mere 20 million. And yet, this price tag could never have been paid by the Jewish community. When the original synagogue was built in 1840, there were over 6,000 Jews registered in the city. By 1933, there were still 6,000 Jews, but by 1945 that number had dwindled to 250. When the wall came down in 1989, there were 49 Jews left in Dresden. After unification, the community was revitalized and challenged to absorb Soviet Jewish immigrants, who were granted residency to settle in Germany (in competition with Israel). Germany was eager to grow its Jewish community. With excitement, the President of the Jewish community of Dresden, Roman König, announced that the congregation had grown to 220 members by the mid-1990s. But 220 Jewish members could not afford building a synagogue for 20 million Euros. When the association “Bau der Synagoge e.v.” was founded, the president of the Jewish congregation served on its board, as did the Protestant Landesbishop of Saxony Volker Kress, the Roman Catholic bishop Joachim Reinelt, and the Minister President of the Free State of Saxony, Kurt Biedenkopf. Church and State had decided to build a synagogue in Dresden.

But Pastor Reimann wanted this to be more than a political affair of the state. He wanted to generate popular support. In March 1999 the Catholic periodical Tag des Herrn reported on a fundraising event attended by sixty people from “society, church, and culture.” The newspaper summarizes Pastor Siegfried Reimann’s speech thus:

Every donation counts, everyone should decide how much they can contribute. We cannot expect that everybody donates 1000 Marks, but maybe 50 are possible. Because one thing is obvious: the small Jewish community cannot pay the money that will be needed… We should not forget that it is not the fault of the Jews that they no longer have a synagogue. The destruction of the synagogue, as well as the persecution and the murder of the Jews, is a past that we must all bear together, although we were not personally involved. We must give a response to this history. This is a chance to approach this subject on a personal level and to remember this past atrocity. This is true for each individual, as well as organizations, banks, and businesses. Reimann reminded everyone that the Dresdner Bank was originally a Jewish establishment…[51]

The construction of the Neue Synagogue was presented as a ritual of penitential restitution. Sure enough, the Dresdner Bank increased its donation, up from their original pledge of 50,000 Euros. The fundraising group successfully collected the money necessary to call for architectural submissions. The Jewish community chose the design that was ranked third by the commission, which combined a bunker-like cube structure on the outside, that projects strength and stability, with a lofty interior of iron chain curtains, creating a tent-like feeling. Its modernist design expresses strength and permanence on the outside and fleeting vulnerability on the inside (figure 4).[52]

Figure 4. The Neue Synagogue in Dresden

On November 9, 1998, sixty years after the Semper synagogue was torched, the ground was broken in the same place in a ceremony that commemorated the pogrom of 1938. Exactly three years later, on November 9, 2001, the synagogue was dedicated and the Jewish community moved in. These rituals of commemoration and restitution turn guilt into the ground of new beginnings. Where November 9, 1938 stands as a day of infamy that separated church and synagogue, it was turned into a day of shared memory and commitment to solidarity in 2001. By 2002, the association “Bau der Synagoge e.V.” reconstituted itself as the “Freundeskreis Synagoge e.V.” to keep raising funds for the upkeep of this monumental new building, which the fledgling Jewish community could still not afford.[53] By 2013, the congregation had grown to 700 members and installed the 29-year-old, German born and trained rabbi, Alexander Nachama.[54]

Penance is a perpetrator-centered activity. Building the Neue Synagoge in all of its modernist splendor served German Christian desires for atonement. Their actions, no matter how generous, will never return the dead or repair the rupture. Dresden’s destroyed Jewish community will never rise from the ashes. The architectural design of the synagogue indicates this radical discontinuity. While the cathedral was rebuilt on the basis of the original plans and with the previous materials, the synagogue is a bold, fortified, twisted cube. But for all of the “impure” self-serving motivations, the church activists’ commitment to connect the rebuilding the Frauenkirche with the construction of a new synagogue also set powerful signals against supersessionism. For the first time in Christian history, the future of Jewish religious life became integral to the Christian presence in the public sphere.

On the Jewish side, despite well-deserved suspicion and doubt, the persistence and consistency of penitential restitution, albeit always a minority position, is acknowledged.[55] Rituals of penitential restitution are performed without reference to sincerity of the emotion or state of mind. Its power rests in its enduring performance. When the Reparations Agreement between West Germany and Israel, known as Wiedergutmachungsabkommen, was signed in 1952, riots broke out inside and outside of the Knesset, the parliament of Israel. The German term for reparations, “making good again,” alone was enough to drive 15,000 people into the streets of Jerusalem to protest the payment of blood money. And this deal, while politically necessary for diplomatic reasons, was not at all popular among the German public either. The majority of German tax payers resented reparations payments as they struggled to rebuild war-torn cities and a ravaged economy. Civil servants, judges, and administrators made the process of filing claims for stolen property, pension funds, and insurance claims a humiliating nightmare for survivors. German resistance to restitution and reparation was massive and wide spread, though considerably better than what survivors encountered in Austria and other European countries, where violence greeted their attempts to reclaim their homes (e.g., the pogrom in Kielce, Poland). While the treaty to pay reparations to the Jewish Claims Conference and the state of Israel was made primarily for expedient reasons of diplomacy rather than moral repugnance or repudiation of antisemitism, the depth and degree of engagement changed over time. Restitution is now more actively embraced by individuals, businesses, organizations, and municipalities than at earlier times. Those who choose to accept the obligations of the past find reparations a worthwhile investment in the future.

Germany has worked hard to turn itself into a welcoming place for Jews, not despite but because of its past. Dresden is one such example, important to note not least because the former East Germany is increasingly characterized by images of xenophobic, racist, nationalist, and antisemitic demonstrations. The rise of the right-wing party AfD and the Pegida movement shape the media perception of the former East Germany as the unrepentant part of Germany, which is hostile to for-eigners, Muslims, and Jews.[56] The presence of these movements is as much a reality of reunified Germany as the citizens’ initiative that built and sustains the Neue Synagogue. There is vandalism, as well as need for permanent police presence in front of Jewish institutions in Germany, which is both disconcerting and reassuring to people who live, work, and pray in these buildings. The recent terrorist attack on the synagogue in Halle on Yom Kippur exposed security flaws and confirmed the need for vigilance and protection. Jewish life in Germany is far from normal, and there is much to feel ambivalent about.

The reality of absence is a constant reminder of the horrors of the past. For instance, the Jewish cemetery of Dresden was one of the largest in Saxony, with over 3000 graves. Who shall maintain it? It is volunteers of organizations, such as Action Reconciliation, the children and grandchildren of perpetrators, who weed the graves, maintain the fences, and clean up after vandalism.[57] The Holocaust has made the task of maintaining Jewish cemeteries a Christian obligation across Europe. The transformation of guilt into penitential restitution commits the Church to the future of the Synagogue, however that may turn out to be. This rapprochement between Church and Synagogue might well have happened without the destruction of European Jewry. But in the aftermath of this cataclysmic rupture, acceptance of responsibility for “The Longest Hatred” becomes the starting point of Christian theology and practice. Recognition of guilt (contrition), commitment to truthful accounts of anti-Judaism (confession), and consistent practice of solidarity (satisfaction) can digest this poisonous legacy and turn its toxic remainders into new ground for a Christian theology of respect for the Jewish other.